Dawn of the Silicon Gods: The Complete Quantified Case

The evidence for accelerating AI capabilities and why skeptics are wrong.

TL;DR

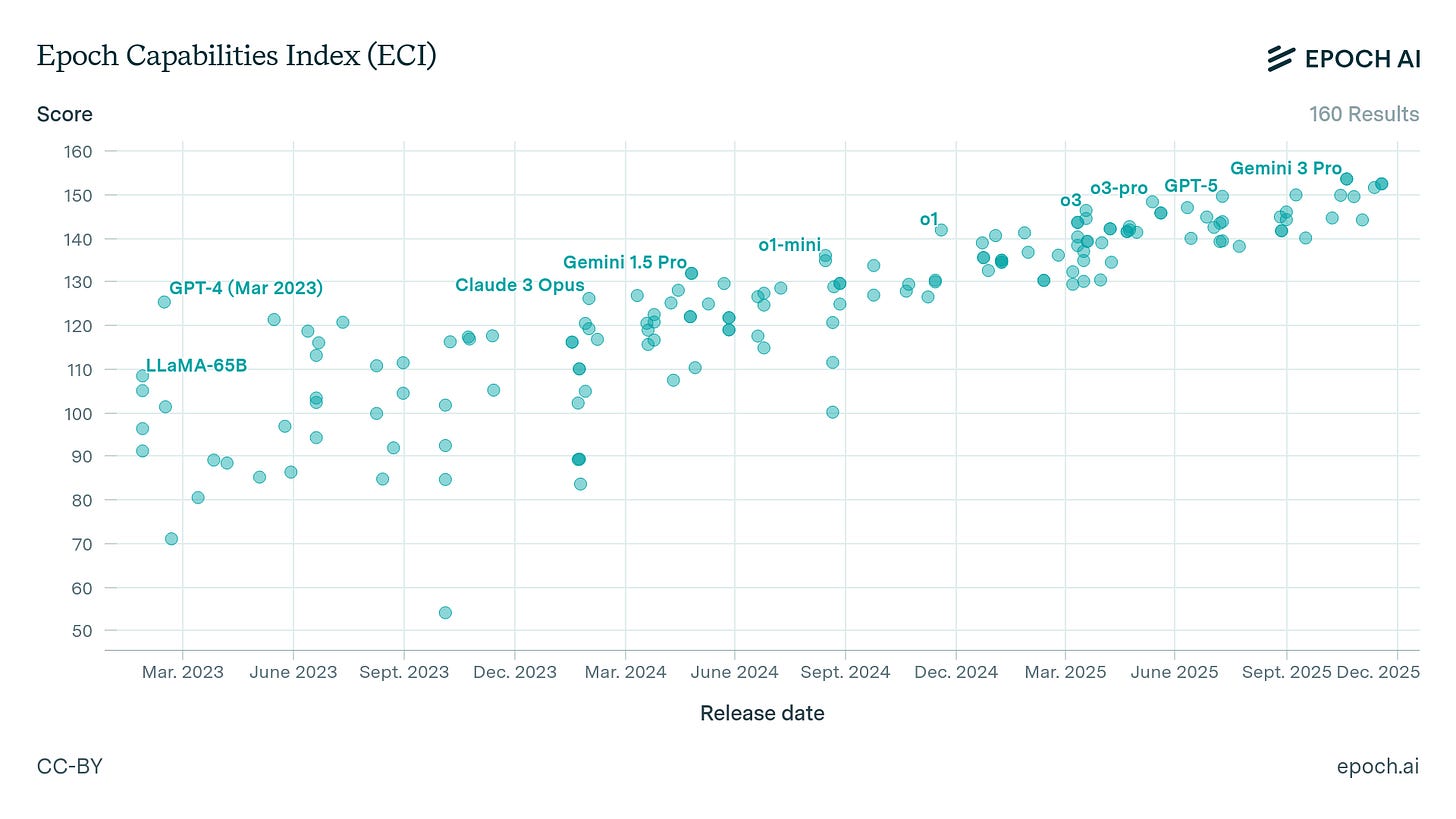

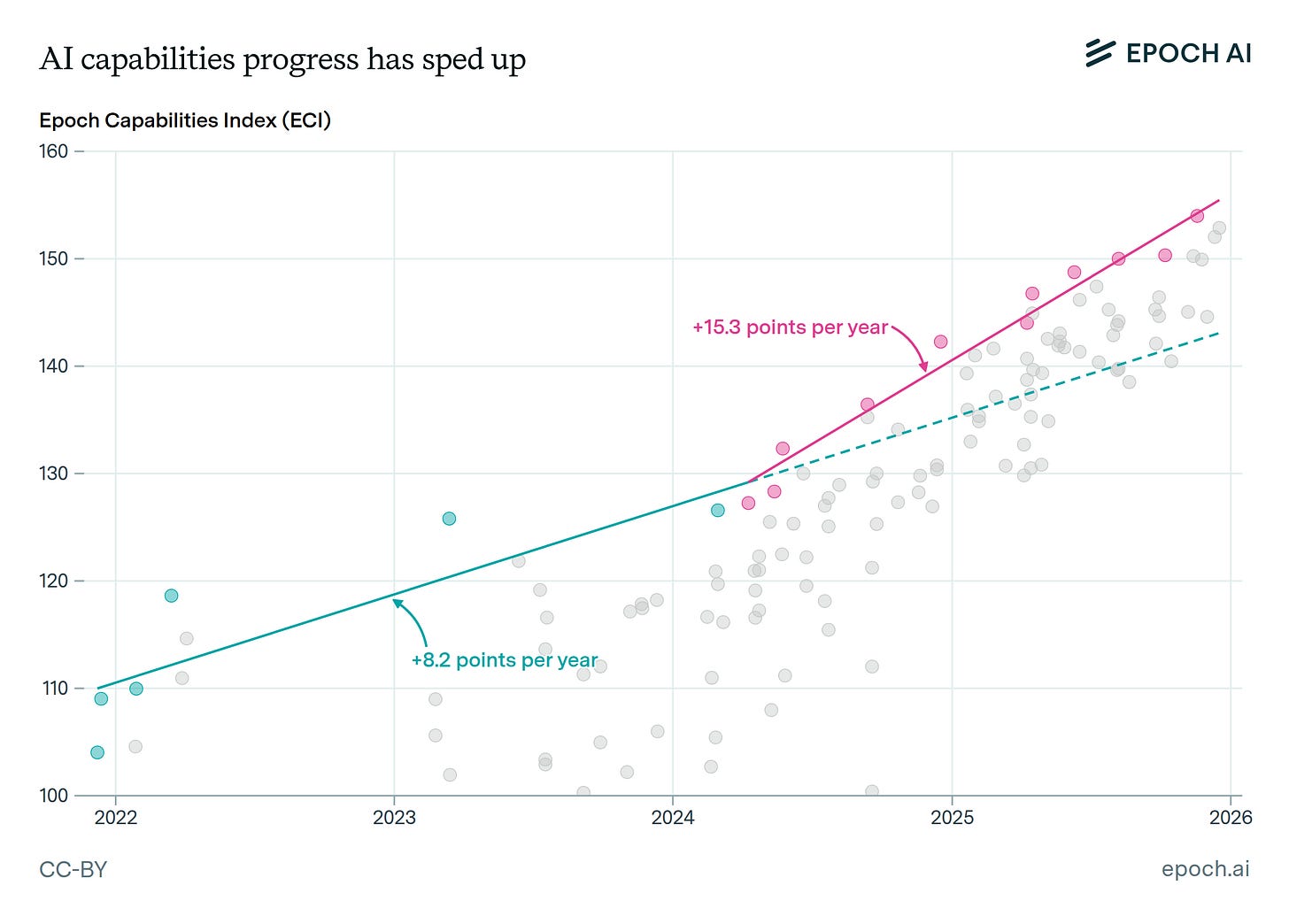

AI capabilities are accelerating. Aggregate benchmark performance shows the rate of progress roughly doubling since 2024.

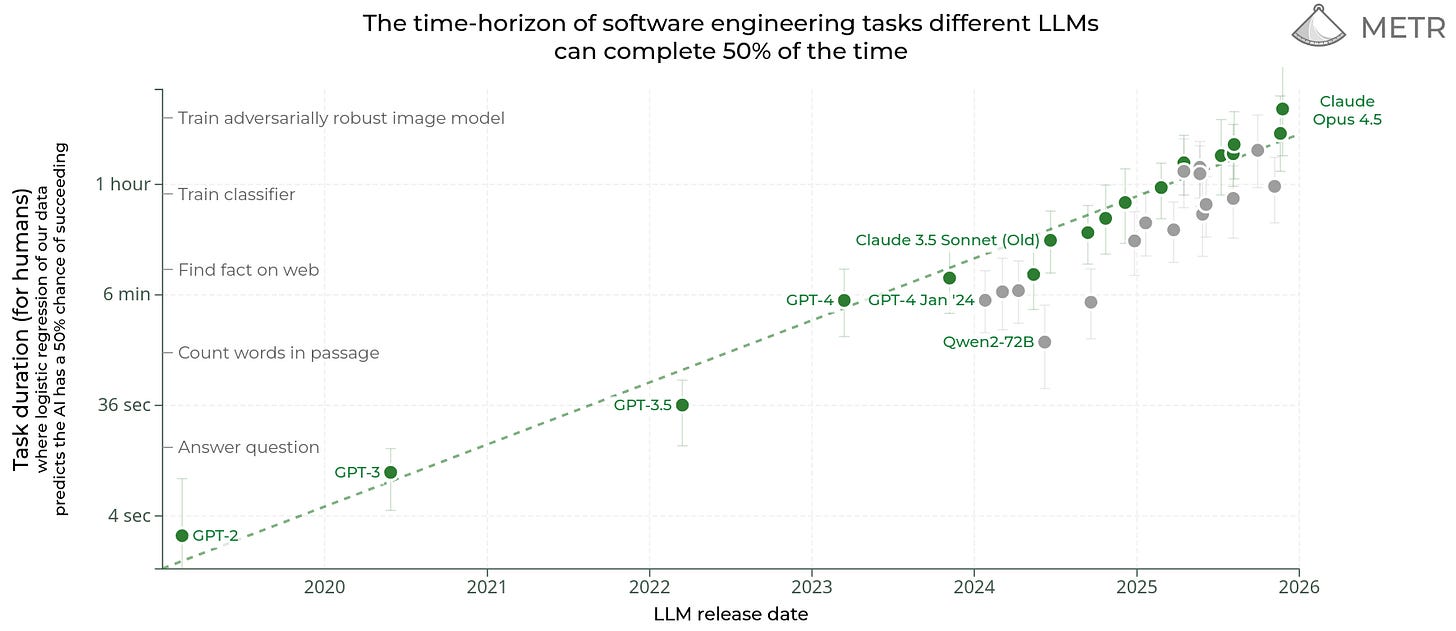

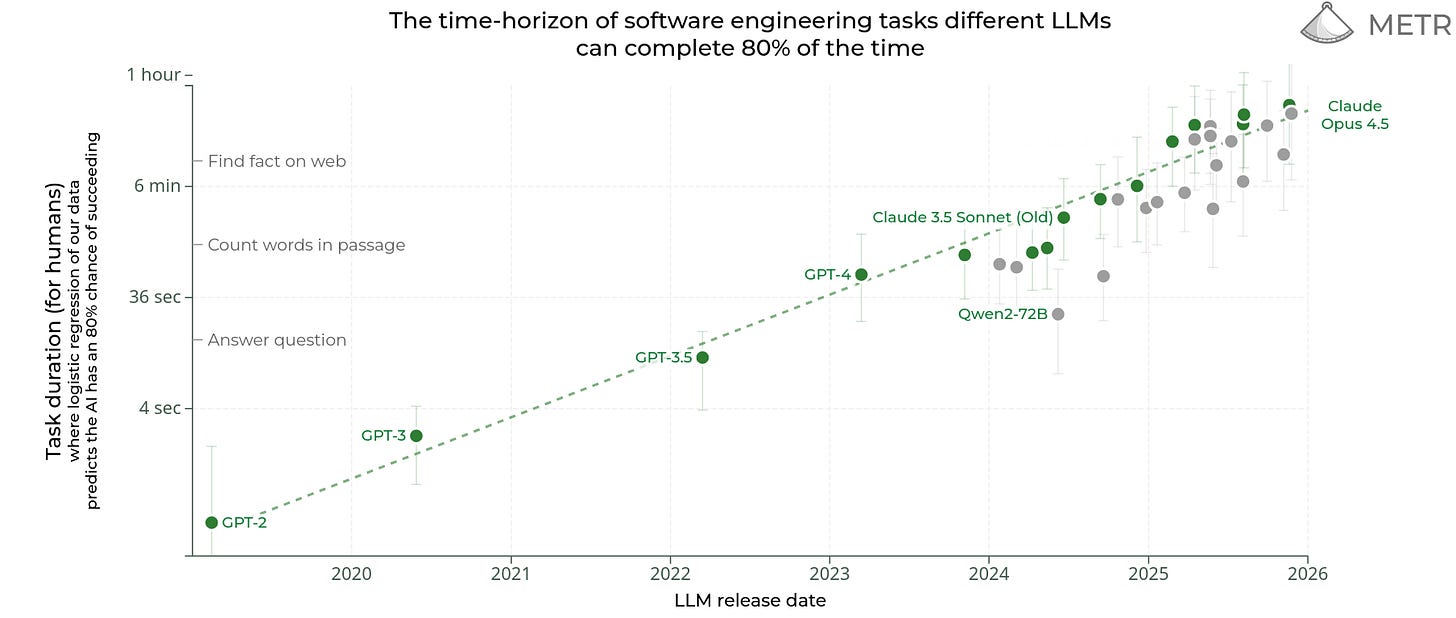

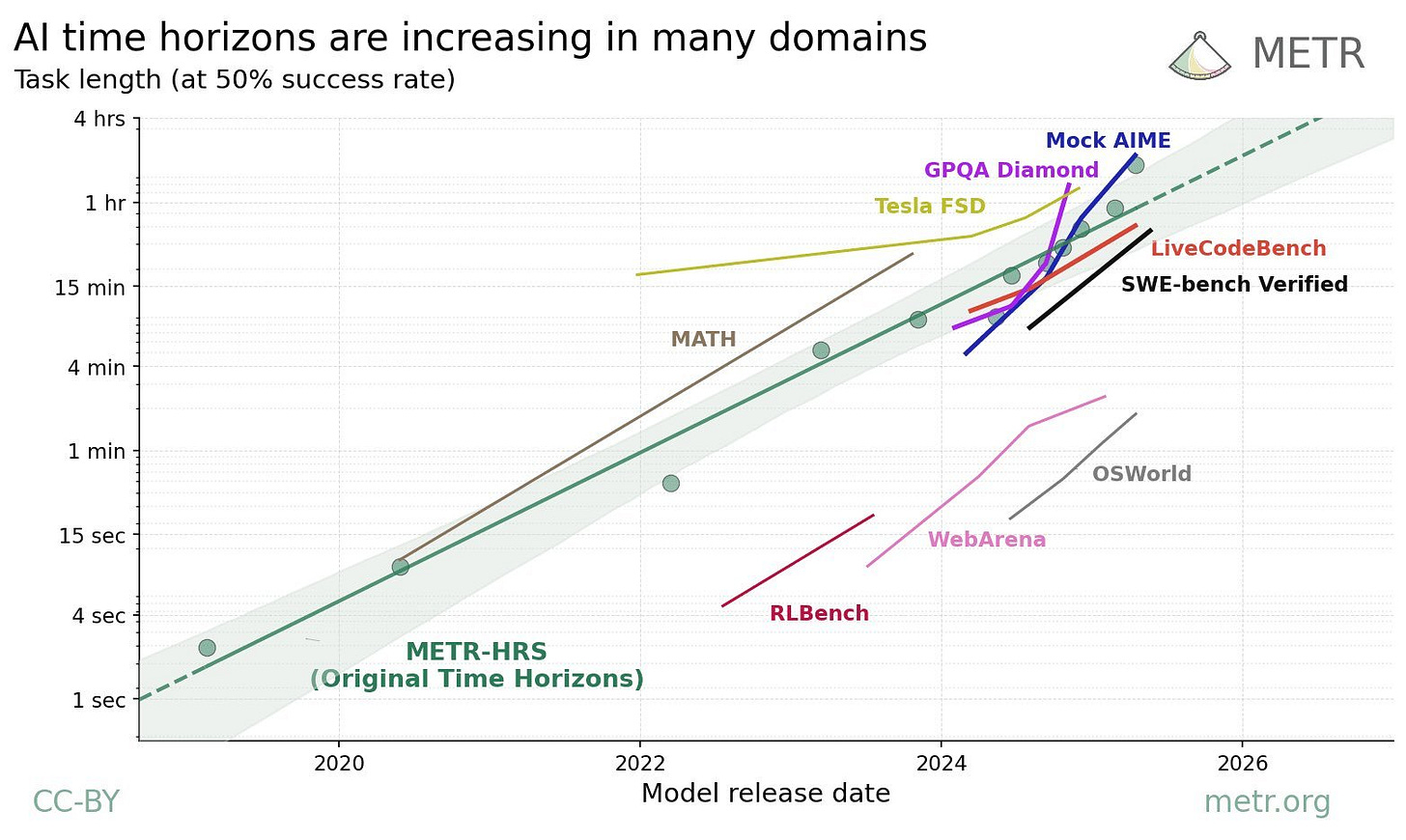

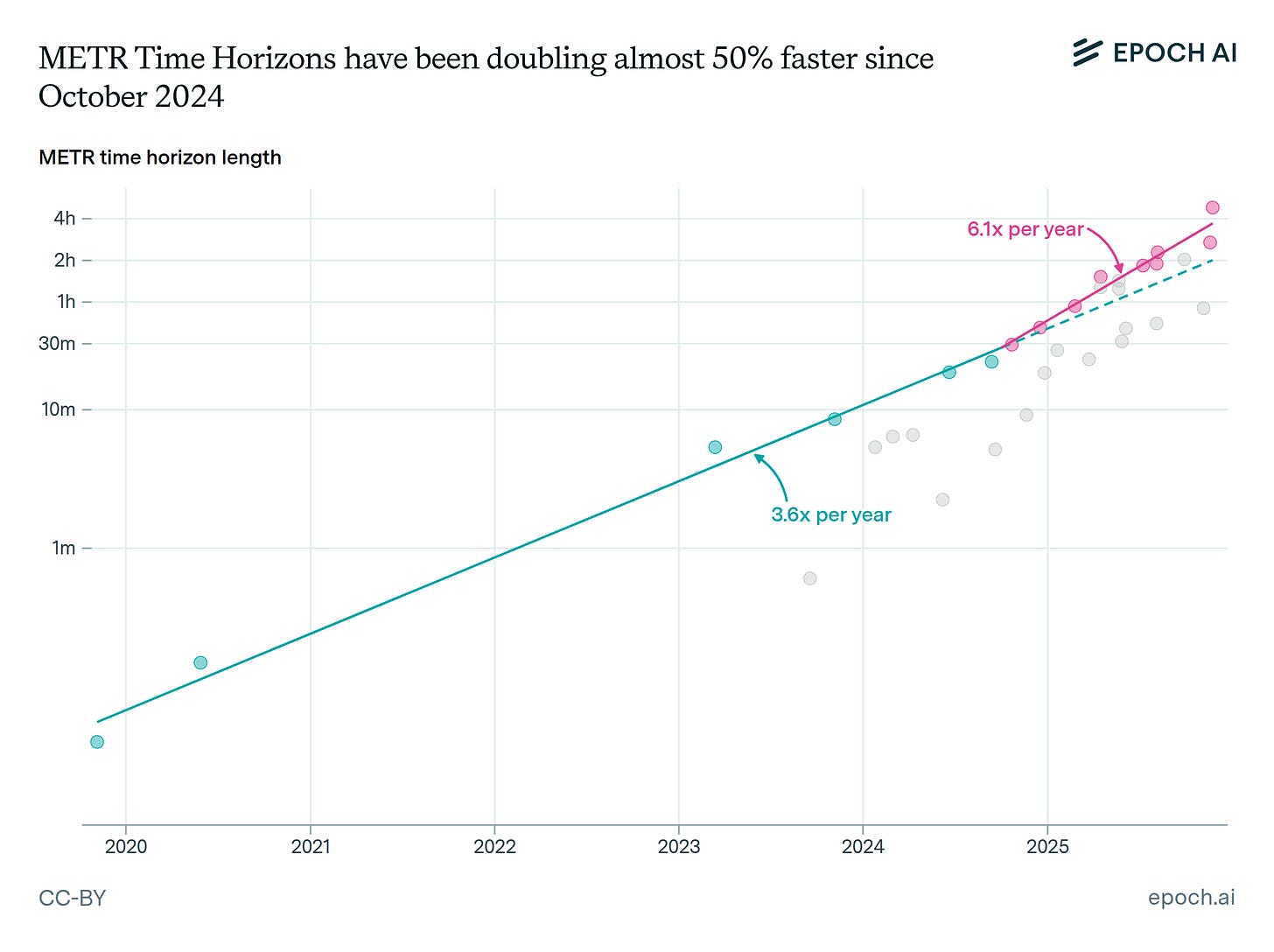

The duration of the longest task AI can autonomously complete (METR) doubles every 4 months.

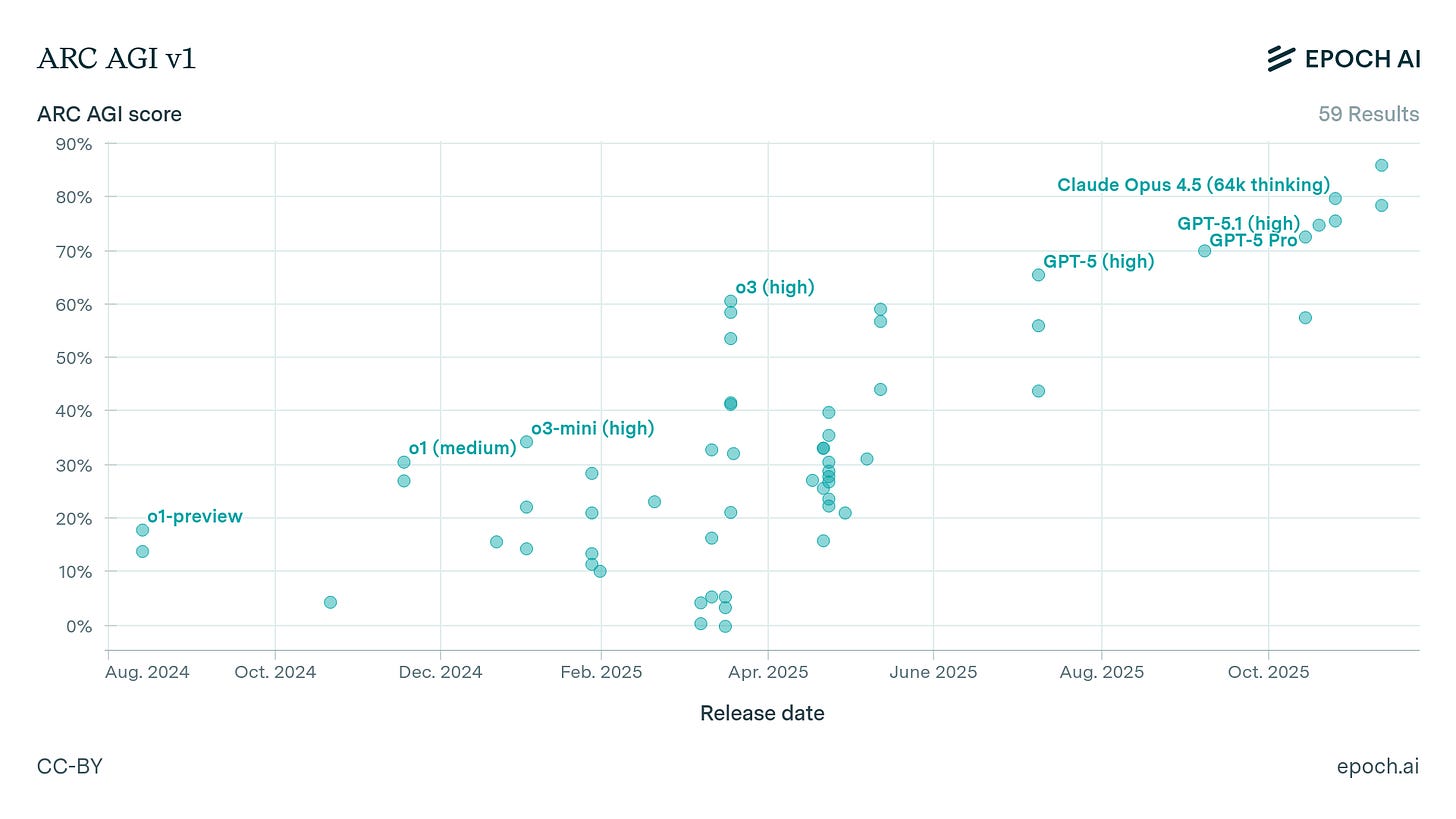

On fluid reasoning (ARC-AGI), AI went from 18% to 86% (human-level) in one year.

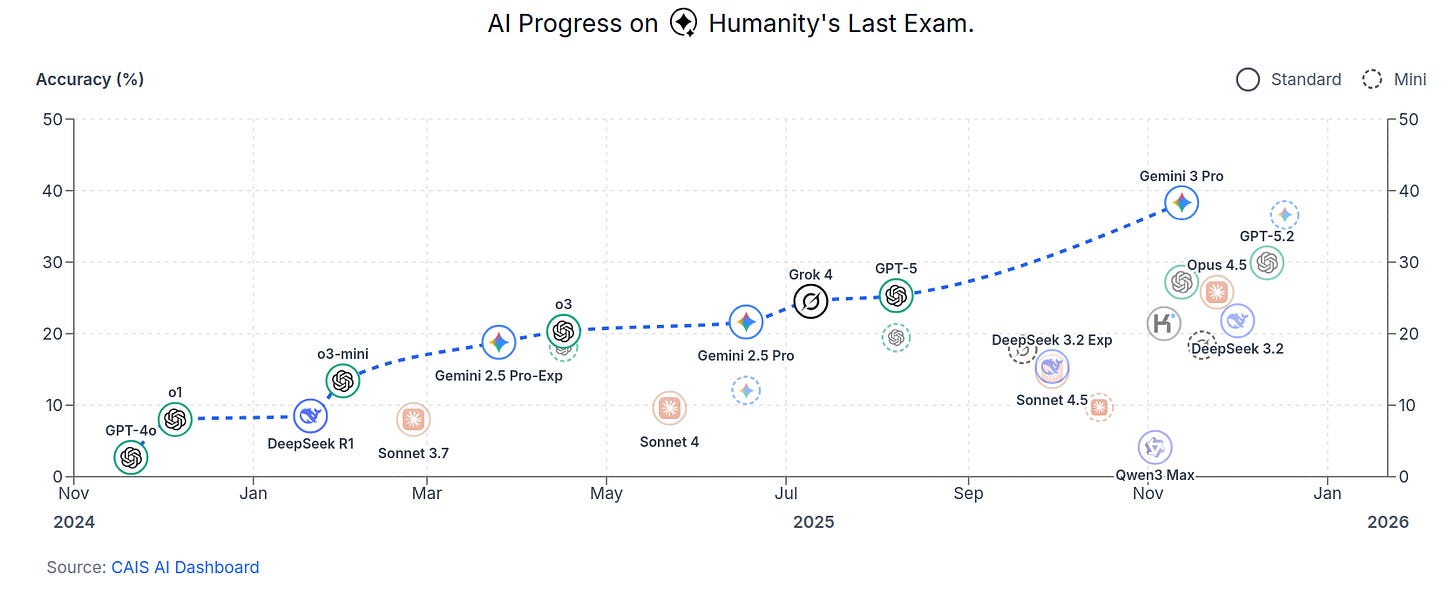

On expert knowledge questions beyond most humans (Humanity’s Last Exam), AI performance increased from <5% to 40%.

AIs have general intelligence. Performance inter-correlates across all benchmarks, just as human cognitive abilities correlate across all cognitive tests.

AIs moved from next-word prediction to direct problem-solving. This produced emergent reasoning: models spontaneously began thinking before answering.

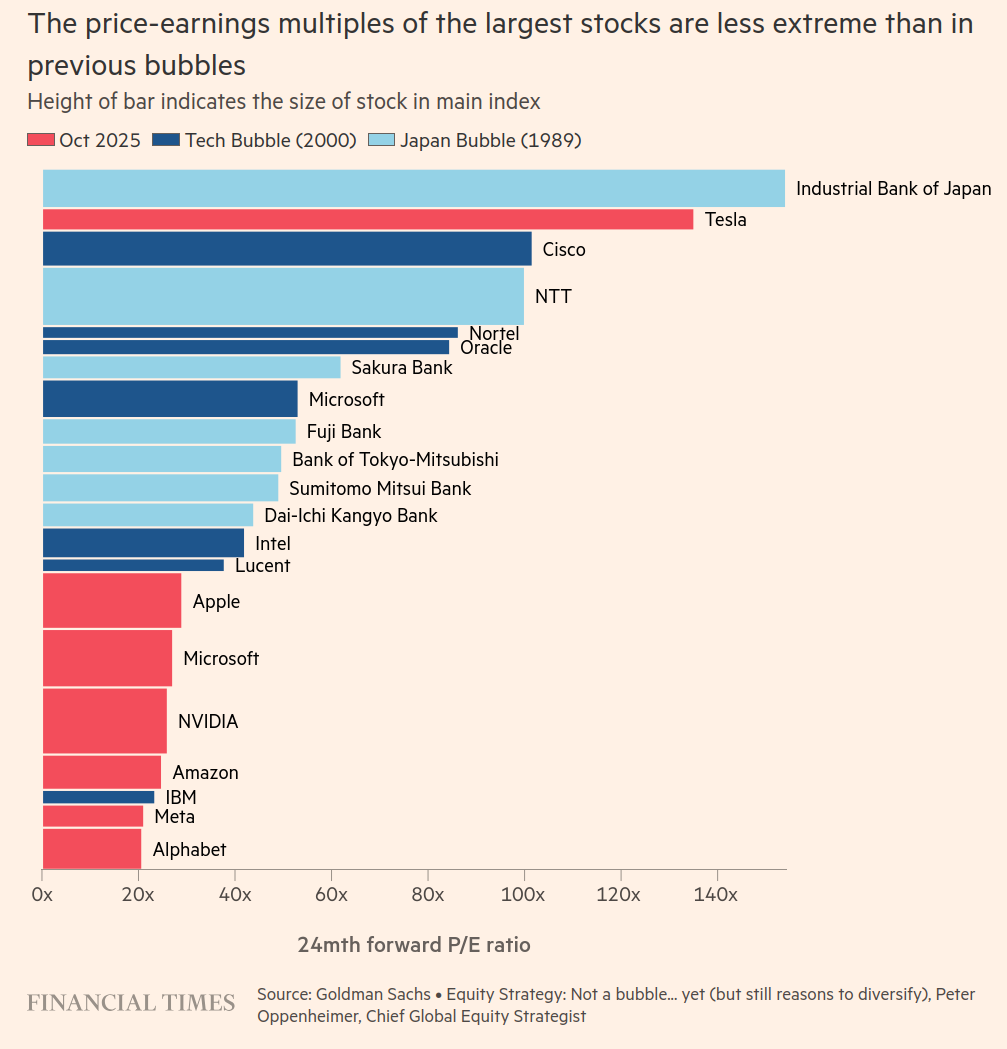

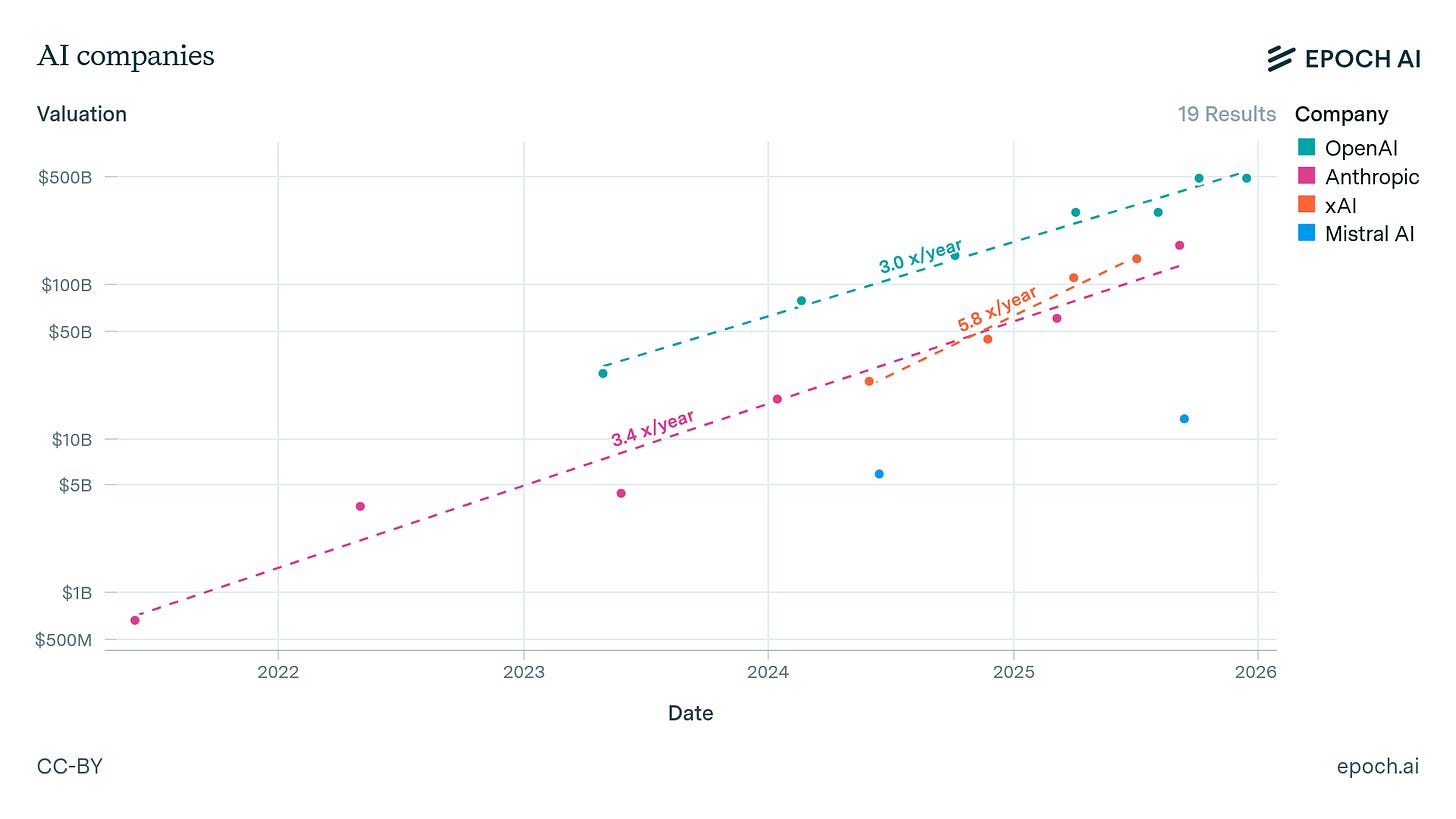

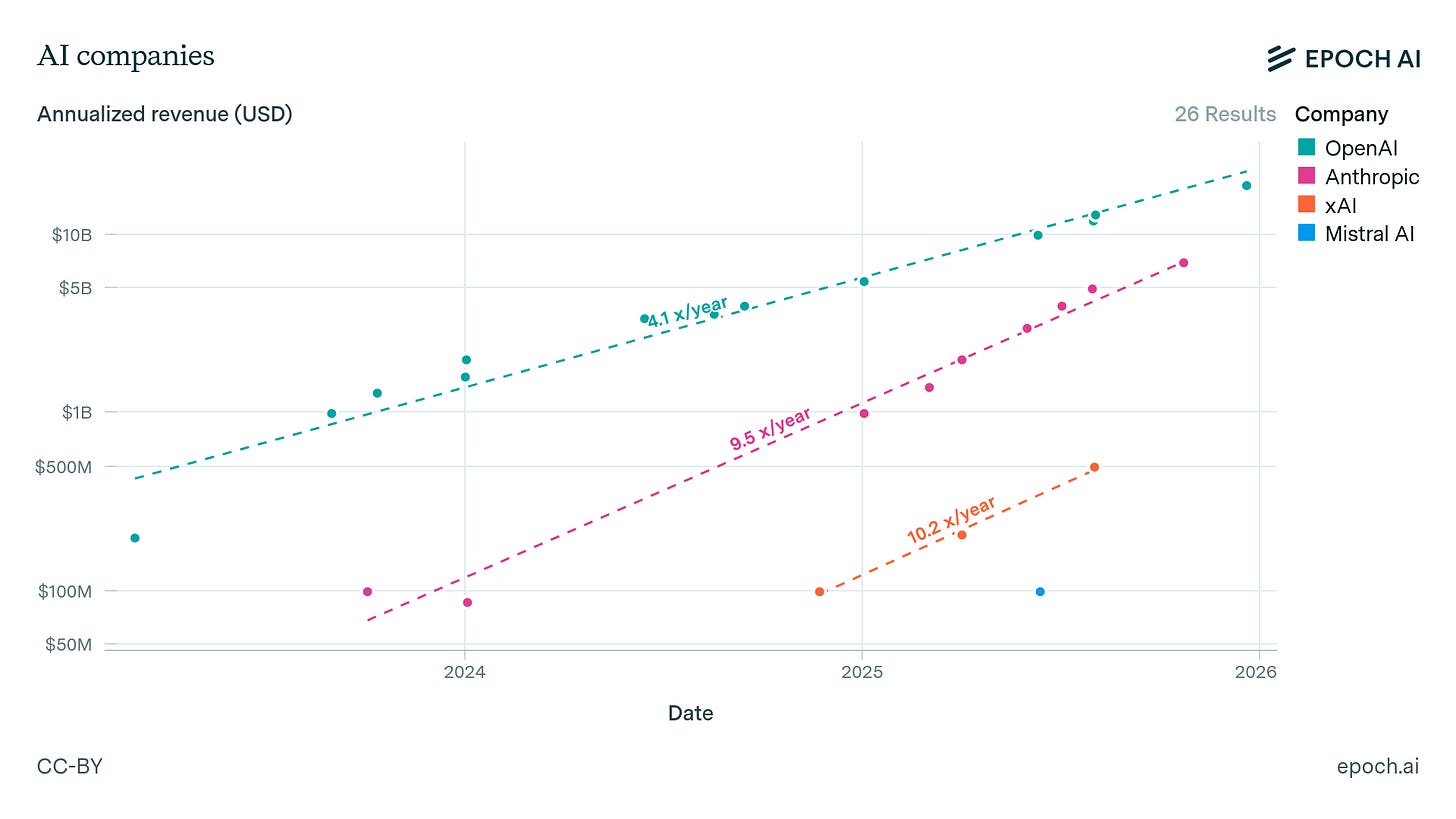

Company P/E ratios are half those of the dot-com era. Across AI companies, revenue grows faster than valuation (~4x/year vs ~3x/year). Enterprise API spending doubled in six months. Total AI output across major providers via API increased 9x in 8 months to ~0.75 trillion words per week.

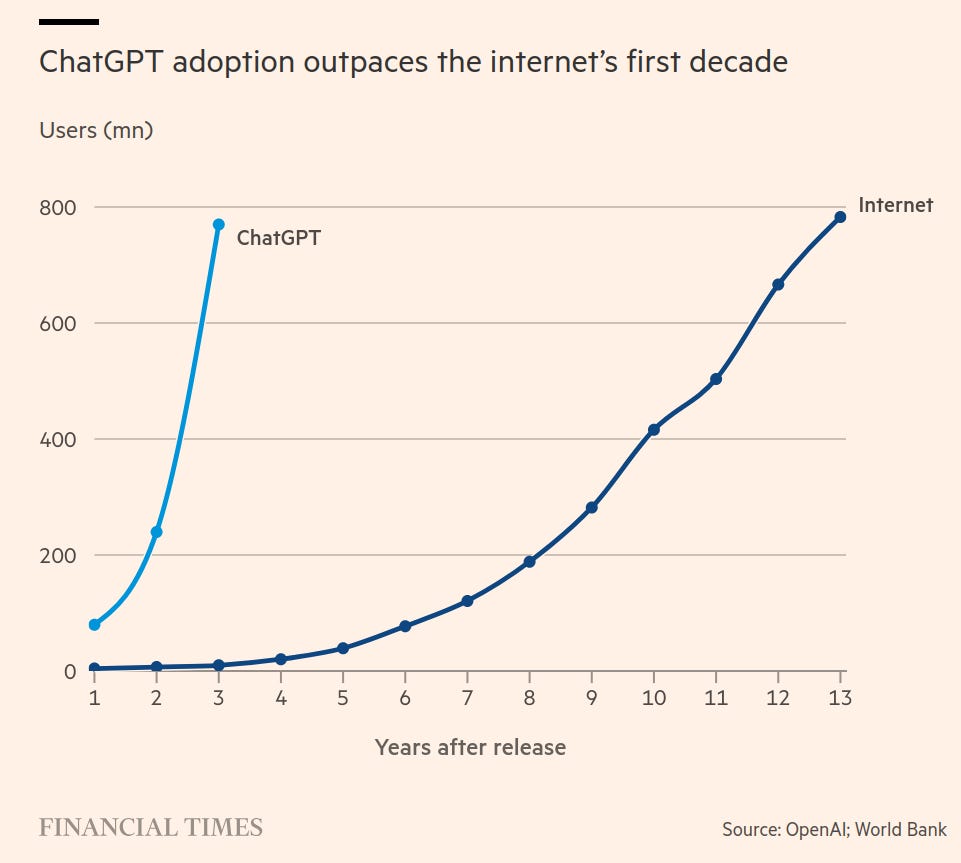

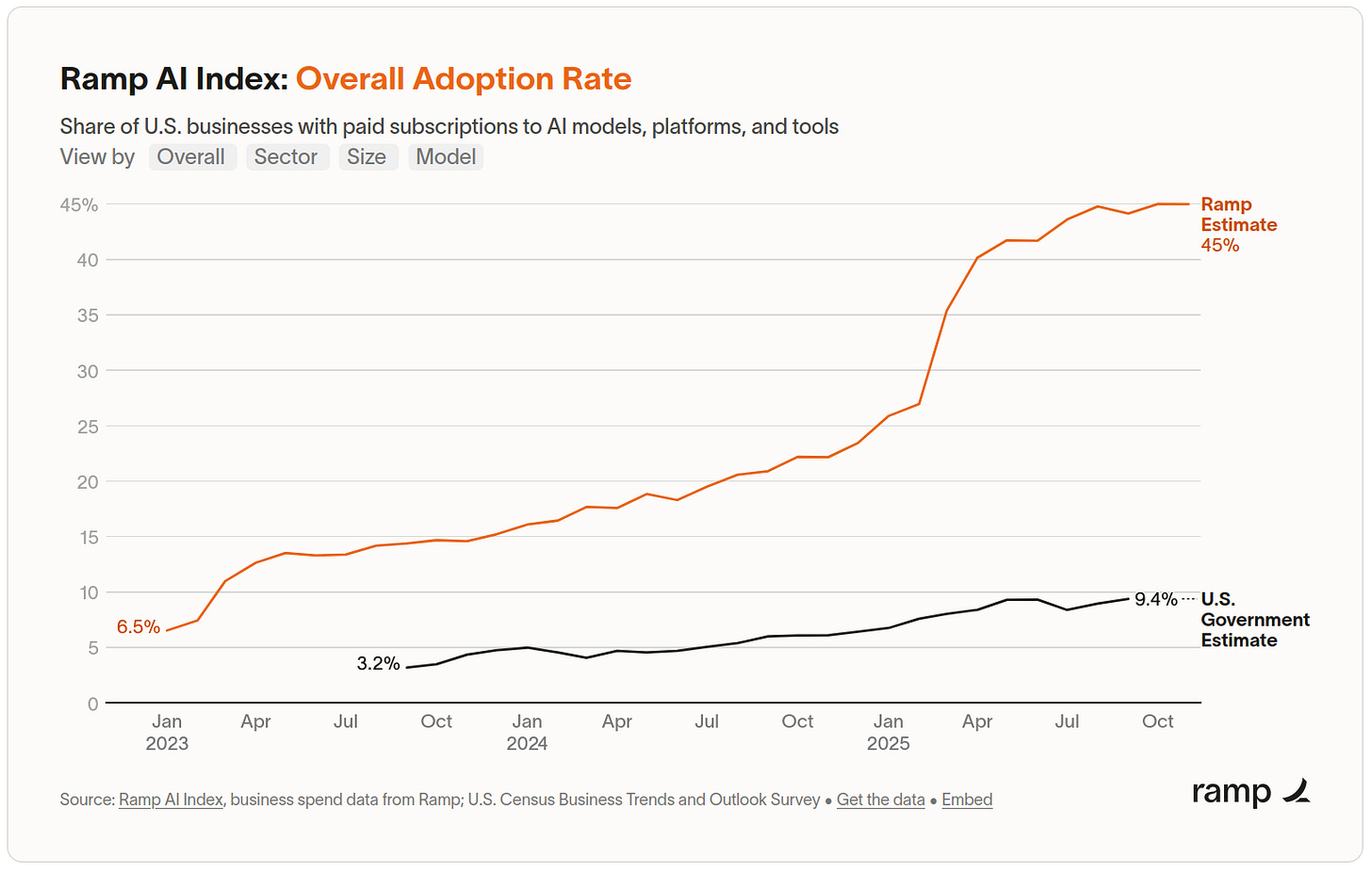

AI adoption outpaced the internet. Worker usage doubled 2024-2025. US businesses with paid AI subscriptions went from 26% to 45% since January 2025.

GPT-4 level intelligence now costs 1,000x less than three years ago, with similar deflationary trends at other capability levels.

Introduction

A new age is dawning.

AI capabilities are advancing faster than most realize. Progress on benchmarks has accelerated since 2024, driven by a fundamental shift in training methods. The economic adoption is real: billions of users, exponentially growing enterprise use, productivity gains measurable across professions. The bubble arguments don’t hold.

This article makes the case systematically.

First, we establish that AI possesses general intelligence. Using item response theory (the same statistics behind IQ tests), we compare AI’s capability structure to human cognition, finding parallels and nuance.

Second, we examine performance on key benchmarks: fluid reasoning (ARC-AGI), autonomous task completion (METR), and expert knowledge (Humanity’s Last Exam). On all three, AI has improved dramatically in the past year, with some approaching human-level performance at a fraction of the cost.

Third, we document the acceleration. Both METR’s time horizons and aggregate performance across all benchmarks show the rate of progress roughly doubling since 2024. We explain why: a training paradigm shift from next-word prediction to directly optimizing for problem-solving through reinforcement learning has produced emergent reasoning, a capability nobody programmed.

Fourth, we address the skeptics. Scaling bottlenecks exist but are surmountable. The bubble arguments fail: P/E ratios are half those of the dot-com era, OpenAI’s revenue is growing faster than its valuation, enterprise API spending is doubling every six months, and worker adoption doubled year-over-year.

If these trends continue, and no fundamental barrier has yet appeared, human-level AI across most domains arrives within this decade. The implications are difficult to overstate.

Understanding AI’s Intelligence and Progress

Epoch Capabilities Index: AI’s “IQ”

Intelligence is a concept, IQ is a test, and ‘g’ (general intelligence) is a statistical phenomenon. Performance on all cognitive tests correlates, and IQ tests attempt to extract the construct underpinning this: general intelligence, or ‘g’. AIs do not lack general intelligence.

Using item response theory, the same statistics behind IQ tests, Epoch AI published the Epoch Capabilities Index, an “IQ” for AI. The score is based on 1103 benchmarks across 126 AI models (Ho et al., 2025).

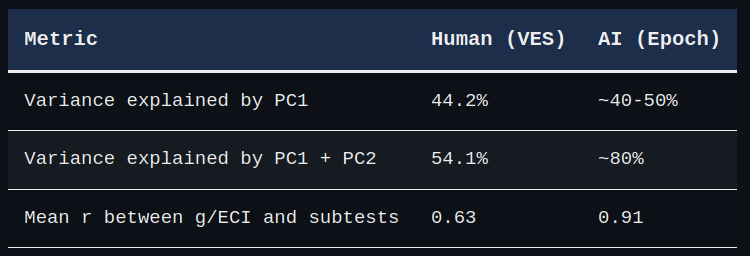

The methodology constructing ECI is similar to IQ tests for humans.1 To analyze the statistical similarities, we compared ECI’s structure to human g extracted from 19 cognitive tests in the Vietnam Experience Study.

On human cognitive tests, performance on each subtest correlates with all others. Epoch AI reports this holds for AI benchmarks:

The table below shows the weights on the different benchmarks in this component, accounting for 80% of the total weight. Note that the *weights are all positive* and not very dispersed.

The first principal component explains similar variance in both human cognitive tests (44%) and AI benchmarks (40-50%). This parallel is meaningful: AI capabilities emerged with a human-like factor structure without being explicitly designed that way.

AI’s tighter factor structure (higher subtest correlations, more variance in the top 2 PCs) could reflect more unified cognition. However, three methodological factors likely explain it:

First, AI benchmarks have hundreds of items versus human subtests with 10-30, reducing measurement error.

Second, model responses are deterministic. Cremieux found insufficient variation in Claude 3’s outputs to construct “IQ” scores between response variations. This determinism is consistent across benchmarks.

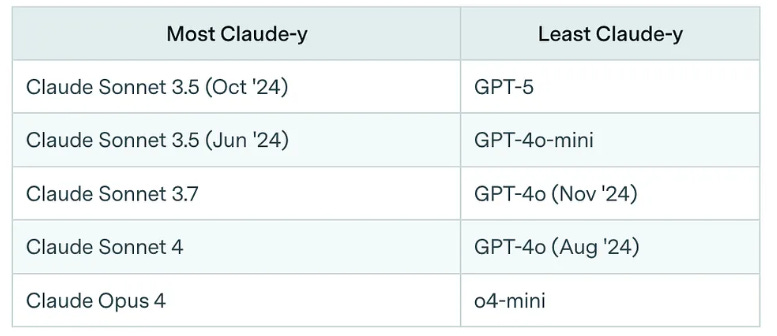

Third, AI models are derivatives of each other (Claude 3 to 3.5 to 4, GPT-3 to 4 to 4o), which explains the large variance in the second principal component. Epoch’s post on ECI shows “Claude-y” (the 2nd PC) is highest on Anthropic models and lowest on OpenAI’s. AI performance captures both general capability and company-specific training focus.

Strangely, on matrix problems Cremieux reported no correlation between the % of humans and % of Claude responses that got each question correct.

This result is suspicious. If it generalized to all cognitive items, there would be no correlation between item difficulty for AIs and humans. Taken to the extreme: is proving the Riemann Hypothesis really no harder than elementary school maths for AI?

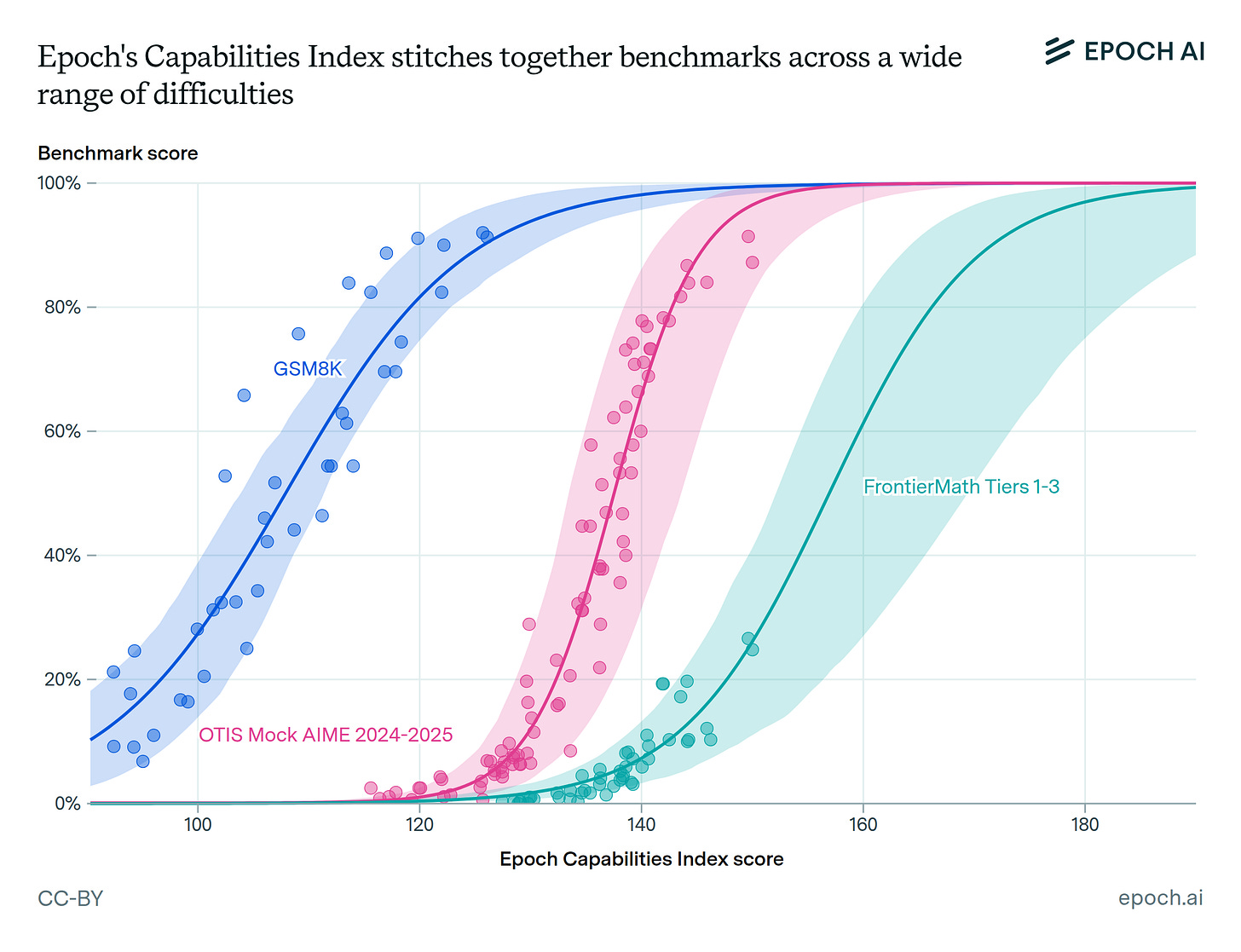

We can test this. ECI performance across three mathematics benchmarks shows that between models, ECI correlates with mathematical outcomes.

As problem difficulty increases from elementary school mathematics (GSM8K) to frontier problems (FrontierMath), praised for their difficulty by Terence Tao, AIs are less likely to solve them. Obviously, humans follow the same pattern. One might argue AIs are just parrots regurgitating memorized answers, but these benchmarks keep questions private to prevent contamination.

But ECI itself is not interpretable. What does an ECI of 140 mean? Or an increase of 15 per year?

To make this concrete, we focus on specific benchmarks: fluid problem solving, autonomous task completion, and expert knowledge. These allow direct comparison to human performance.

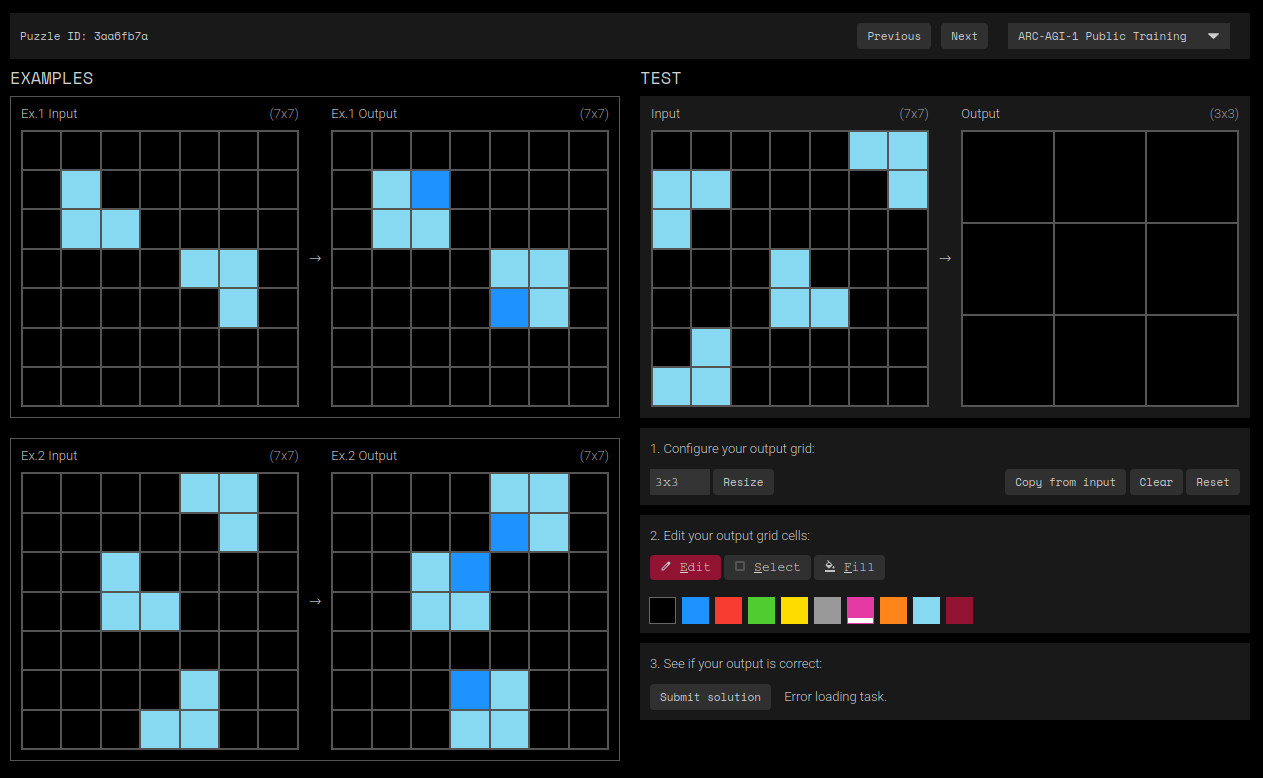

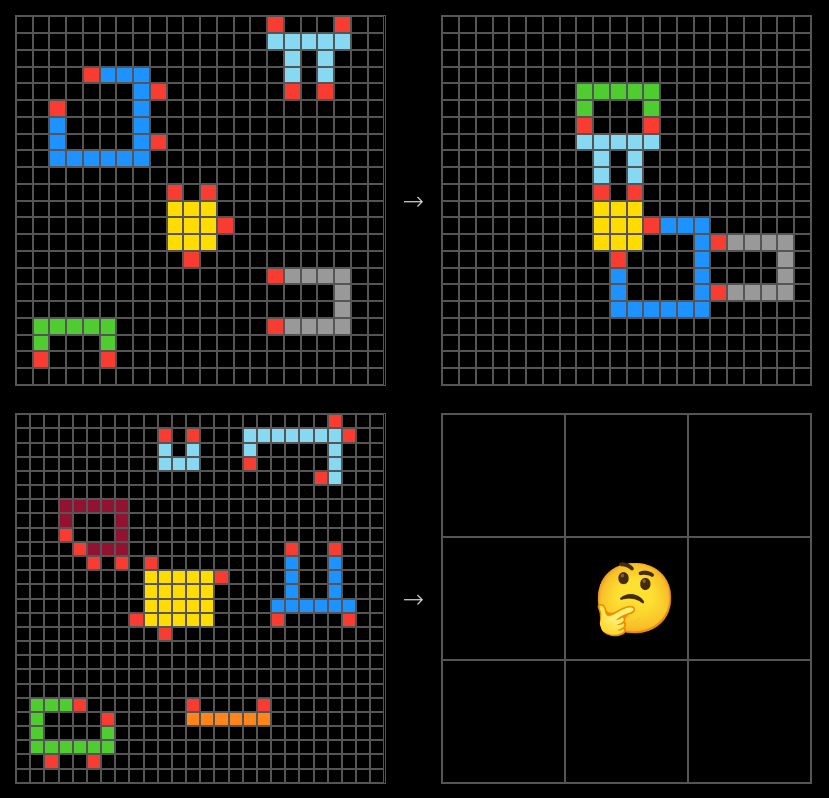

Fluid Problem Solving: ARC-AGI

ARC-AGI is Raven’s Progressive Matrices for AI. It’s arguably better than RPM: not multiple choice, with many possible solutions per problem, so patterns cannot be memorized. It still measures the same core pattern matching ability.

ARC-AGI has two versions: an “easy” benchmark (ARC-AGI-1) and a “hard” benchmark (ARC-AGI-2). Example questions from each:

You can attempt both questions yourself here and here, or take the full test.

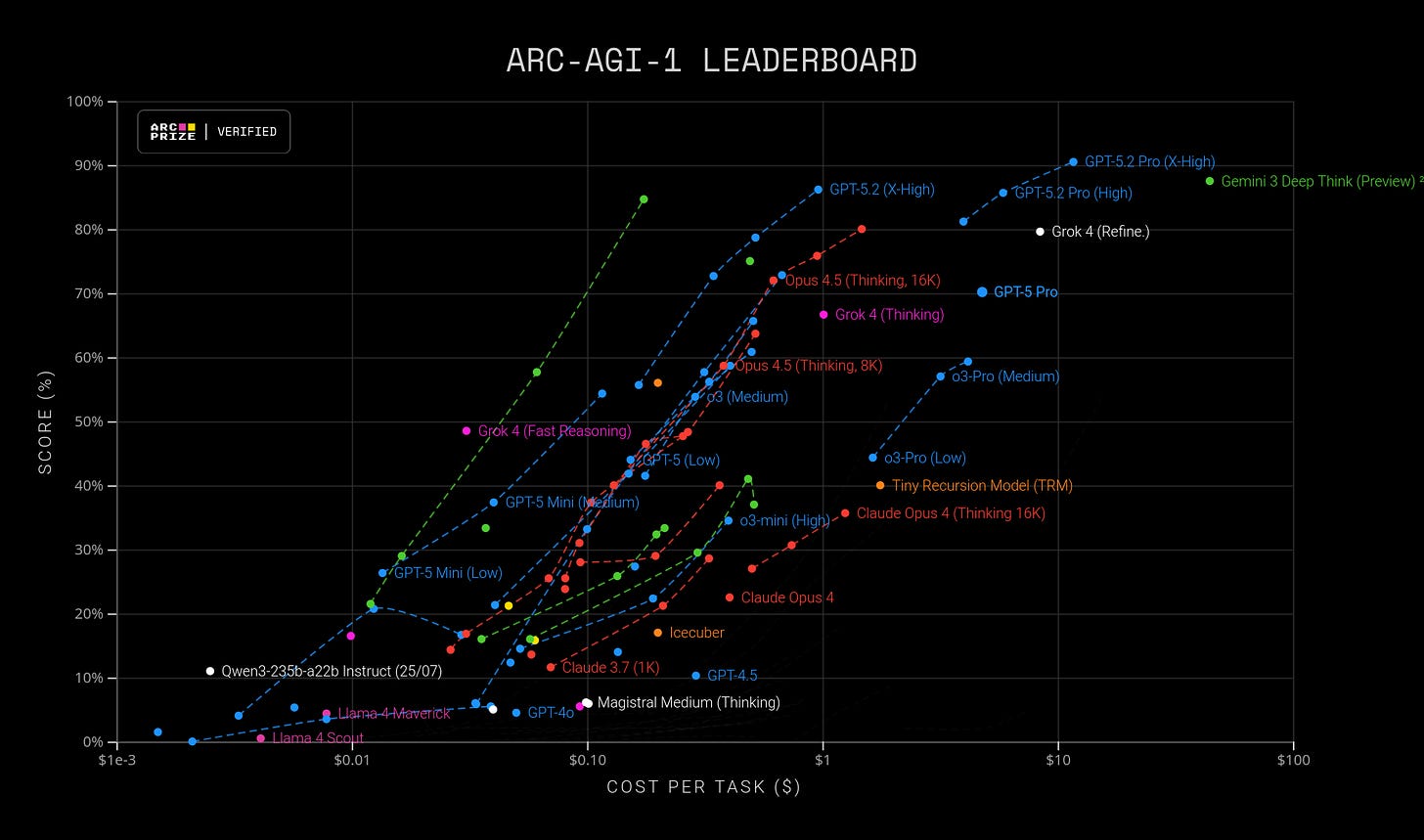

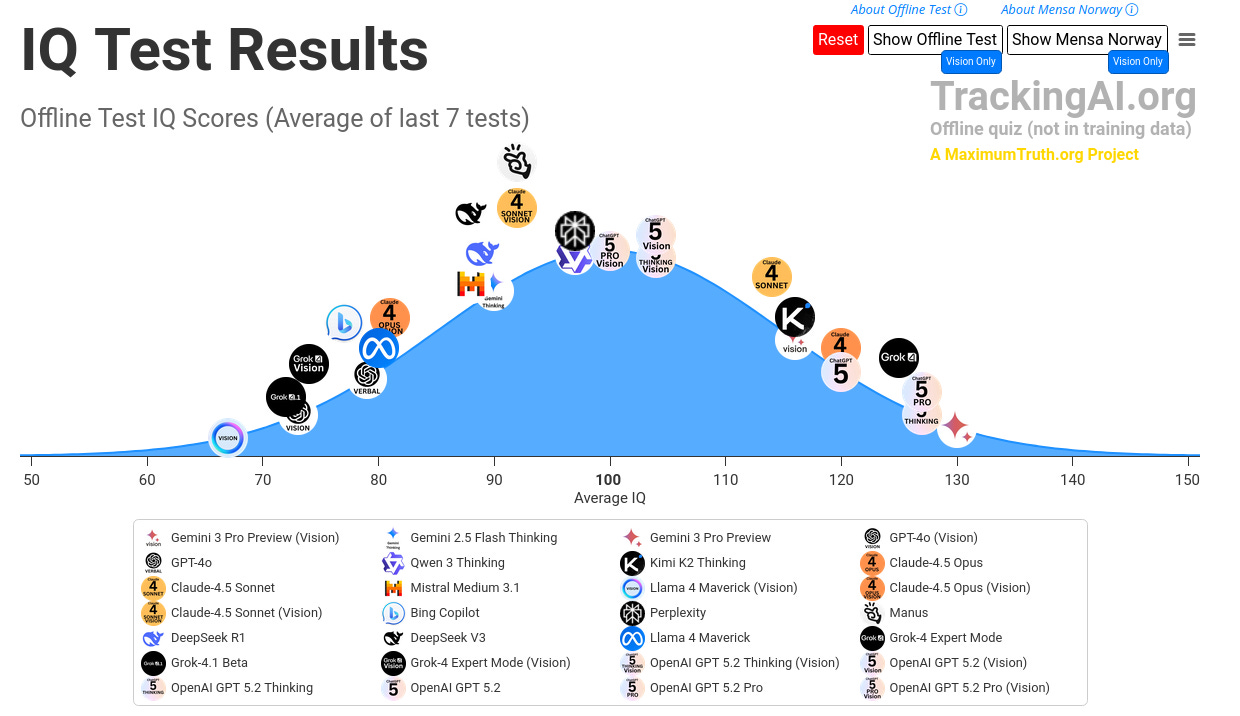

To prevent contamination, AI models are evaluated on a private dataset not accessible to the internet. The current leaderboard shows the general trend: improving performance at declining cost.

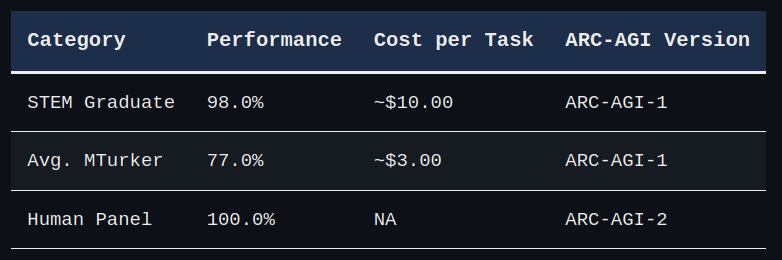

Humans perform well on ARC-AGI. The benchmark was developed to demonstrate that AIs lack true intelligence, that they’re just pattern matching from training data.

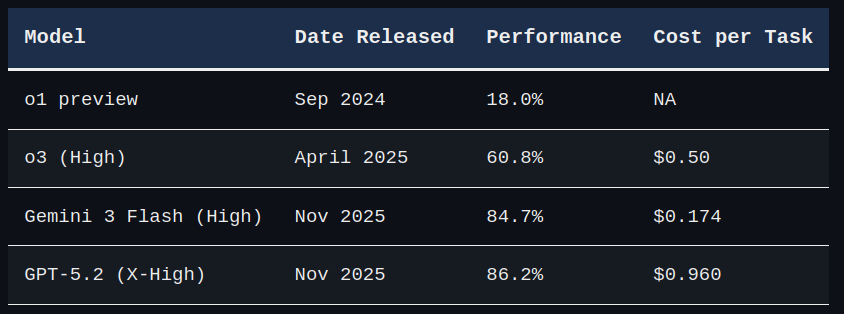

This is no longer true. AI performance has skyrocketed from 18.0% to 86.2% in one year, now matching average human performance at 3x cheaper cost than an MTurker2, or 17x cheaper with Gemini 3 Flash. Benchmark saturation is near for ARC-AGI-1.

At this rate, AI will surpass the average STEM graduate at 3-20x cheaper cost by next year.

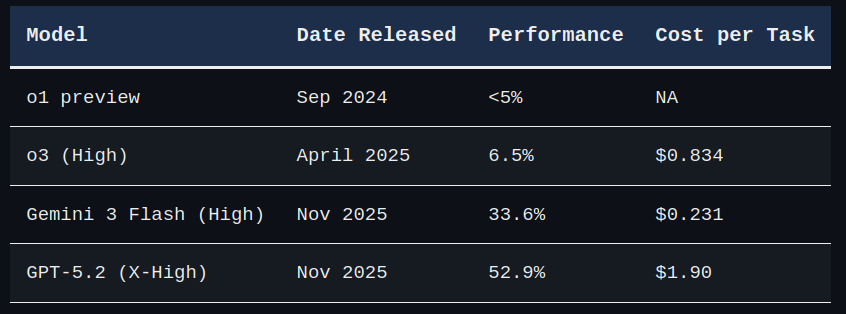

For ARC-AGI-2, AI barely reached 5% last year. Now it’s at 52.9% at a price cheaper than a human.3

We can also use actual Raven’s Progressive Matrices from Mensa Norway. Maxim Lott runs a website where AI models attempt RPMs daily, using a withheld test to prevent contamination. This has become a popular benchmark for comparing AI to human IQ, and is analogous to ARC-AGI.

However, it should not be taken seriously:

An IQ of 100 on this test does not correspond to 100 in the general population. The test reflects a self-selected group.

This is not a full IQ test. Measuring ‘g’ requires multiple subtests, not just RPM. RPM has poor g-loading because patterns can be learned (Krautter et al., 2021).

Assigning AI a human IQ is inappropriate because, as shown above, AI and human intelligence are asymmetrical.

Evo plotted frontier AI models on this Mensa Norway test. Gemini 3 Pro scores an “IQ of 130”, and performance continues to increase even on the withheld dataset.

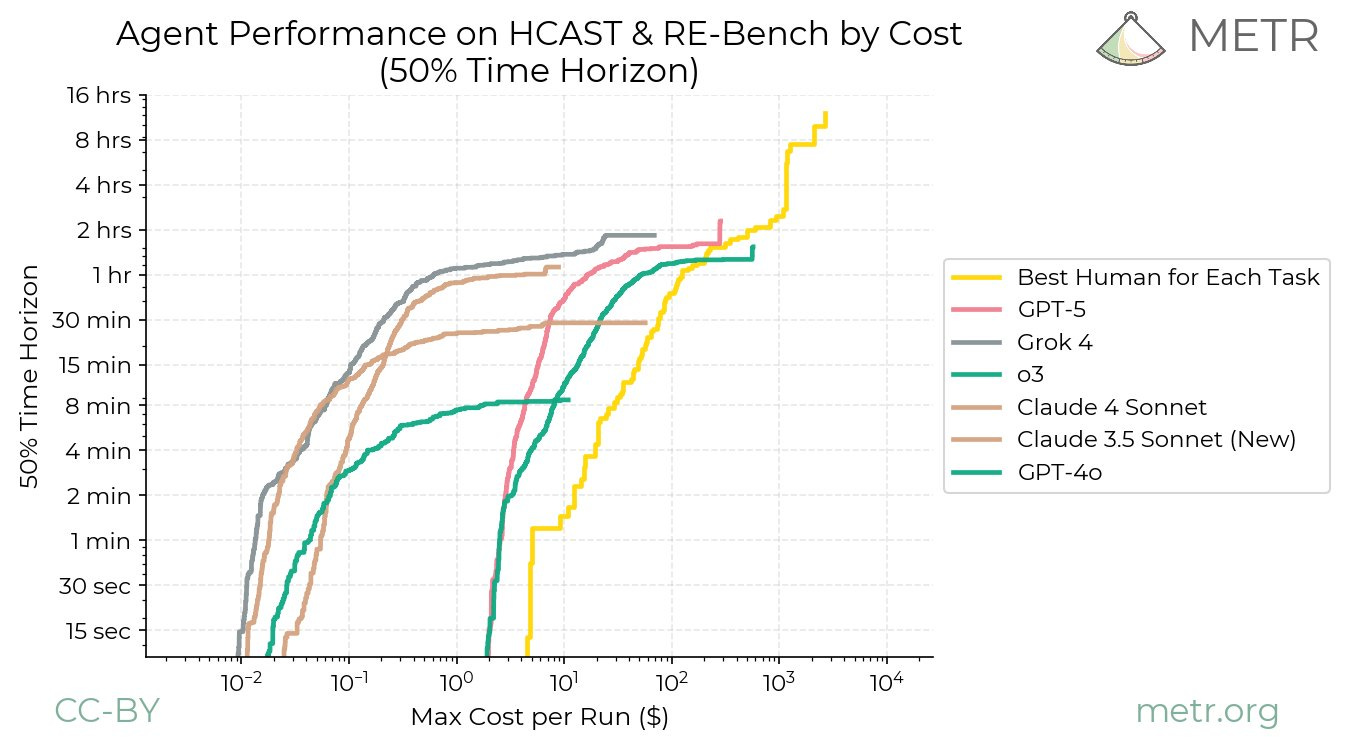

Autonomous, Agentic Ability: METR

AI’s problem solving ability is now at human-average. But problem solving alone doesn’t mean it can integrate into the economy or complete tasks that take weeks or months.

AIs struggle with long horizon tasks for two reasons.

First, context windows. AIs are input-output machines: they take a set number of words and produce output. Context windows are limited to 100,000s to 1,000,000s of words; beyond this, AIs “forget”. The workaround is writing summaries, but AI doesn’t know what’s important long-term. Long-term memory is something AI fundamentally lacks.

Second, continual learning. Humans learn continuously from little information: we’re told what an apple is, feel it, eat it, and remember for years. AI needed most of the internet to learn what an “apple” is. The same applies to skills: a human writing a Substack learns what makes a good post over time. AI lacks this capability due to context limits and data requirements.

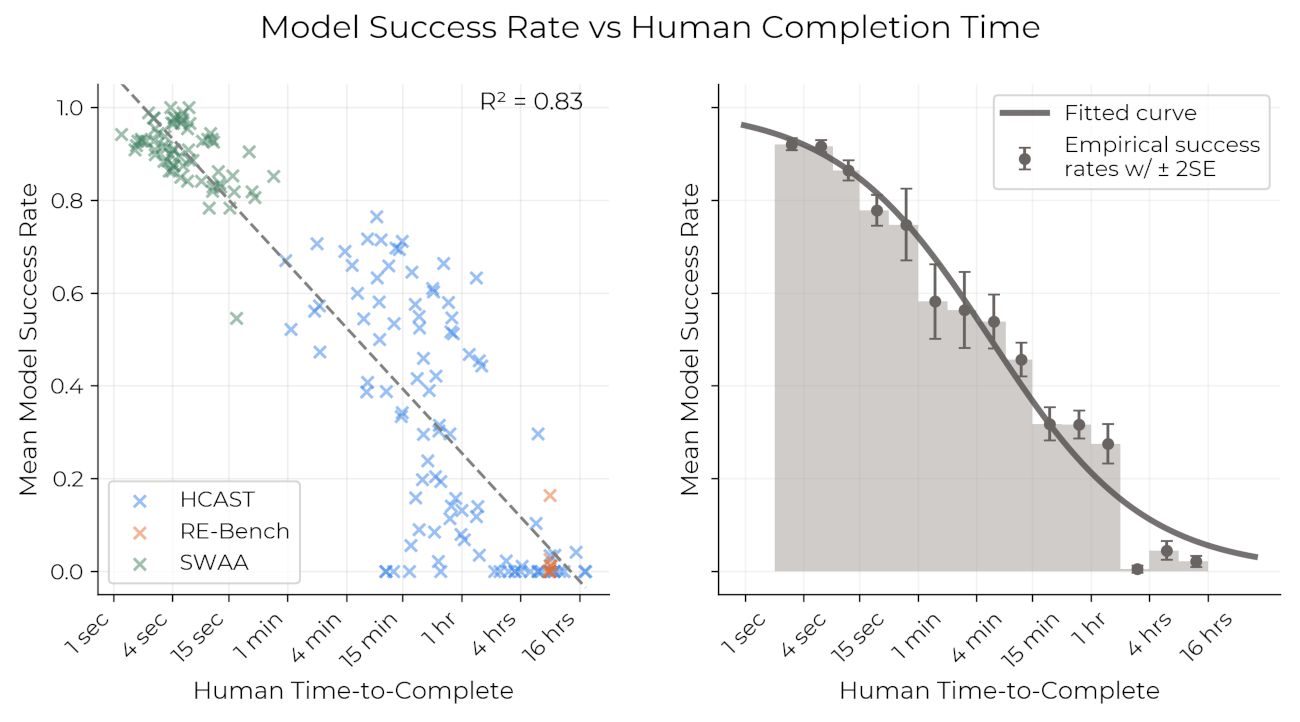

METR’s time horizon benchmark (Kwa et al., 2025) visualizes this. For humans, task cost scales roughly linearly with time. For AI, cost increases super-exponentially with task length.

AIs are faster and cheaper for short atomic tasks, but struggle with tasks taking a day or more.

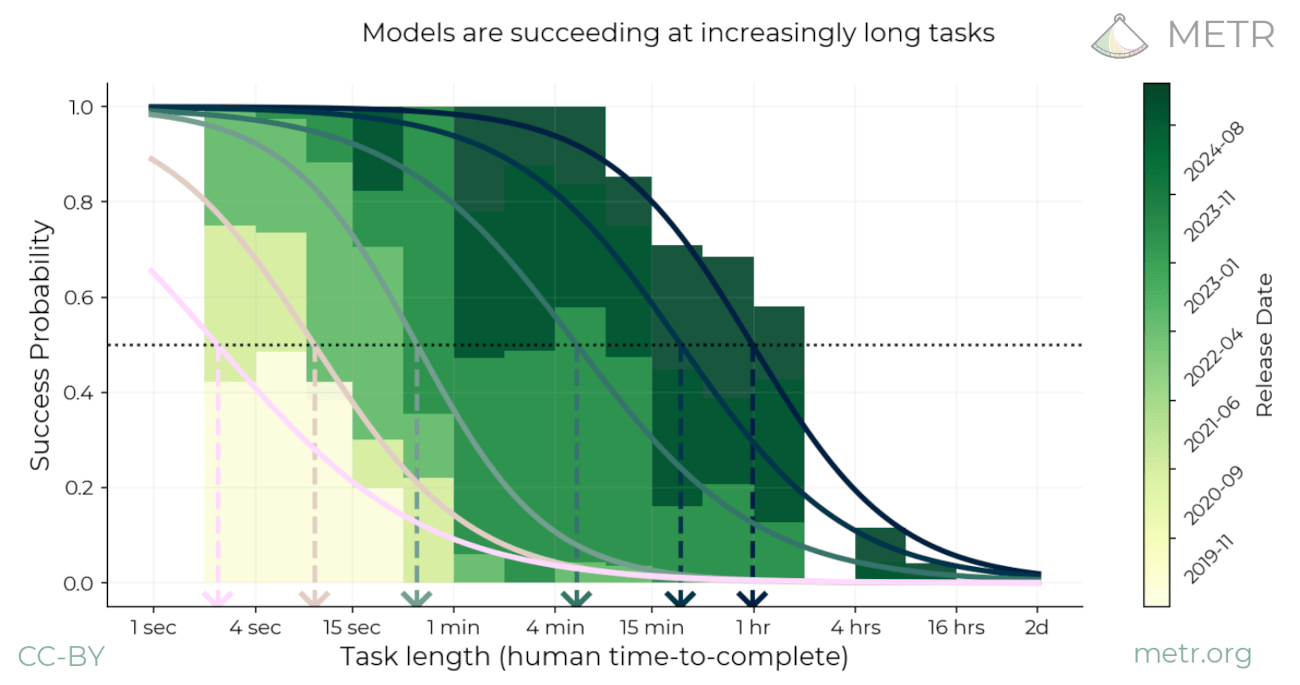

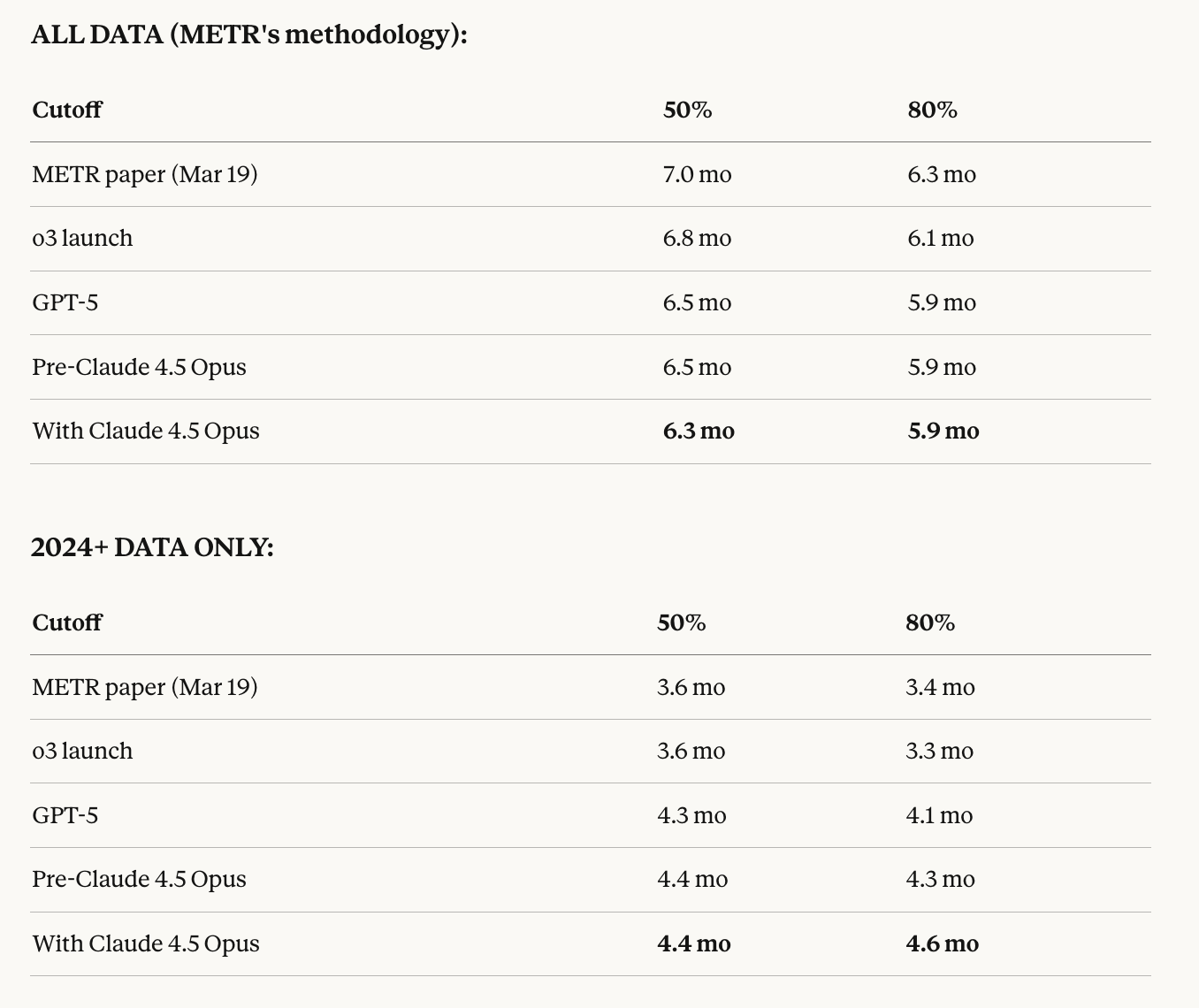

This is changing exponentially. The improvement is so consistent it resembles a “Moore’s Law” for AI. Below are time horizons for 50% and 80% task completion success. The current state-of-the-art: Opus 4.5 at 4 hours 49 minutes (50% success), GPT-5.1-Codex-Max at 32 minutes (80% success).

To calculate time horizon for a single model: they estimate success rate by task time bin, fit a curve, then use the curve to find the time at which the model hits 50% or 80% success.

Plotting multiple models shows newer models shifting the curve rightward, achieving longer time horizons.

The doubling time across this period is roughly 6 months. A piecewise regression from 2024 onwards shows it has shortened to about 4 months. More on this acceleration later.

Like Epoch’s Capabilities Index, METR is a compilation of benchmarks. Breaking it down highlights AI’s asymmetry with human intelligence.

OSWorld, WebArena, and RLBench are visually-based agentic tasks. OSWorld (Xie et al., 2024) tests OS settings, terminal use, GUI data analysis (LibreOffice, Excel), document editing, email, and accounting. On these, AI is ~4 years behind the overall trend. We’re still in the pre-GPT-4 era for computer use via the user interface.

This highlights another limitation. Humans think and act simultaneously; our senses don’t stop when we think. AI does nothing but think when thinking: think → act → think → act. Humans can think+act in parallel.

AI cannot interact with the physical world concurrently. Using an OS with vision means taking screenshots, acting, taking more screenshots. If something unexpected happens between screenshots (a popup, an ad), it fails. This also makes AI awful at video games requiring reaction speed, like CS:GO.

Despite these limitations, progress continues. o3 (April 2025) performed 23% on OSWorld. Eight months later, Opus 4.5 performs 67.1%.

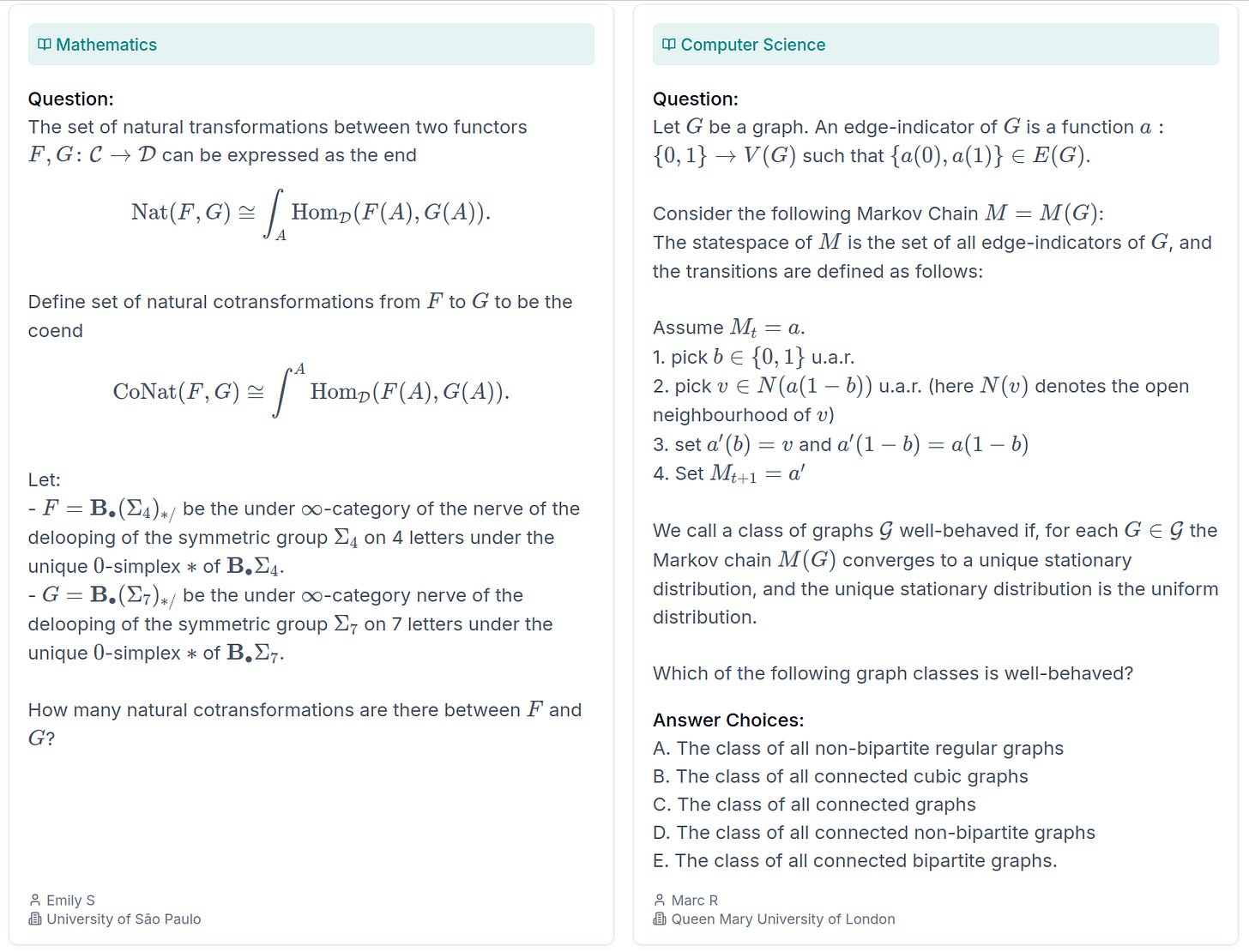

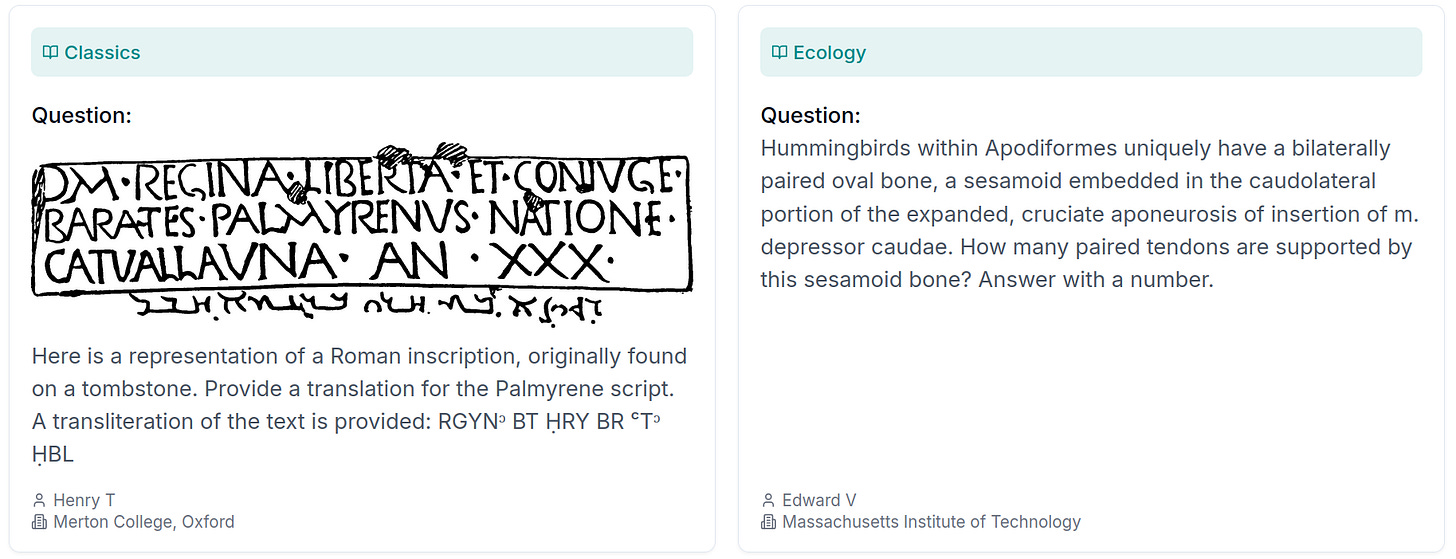

General Knowledge: Humanity’s Last Exam

Unlike agentic tasks, AI excels at general knowledge compared to humans. Trained on the internet and almost all published papers and books, even last year’s o1 scored ~80% on GPQA (PhD-level science questions). Gemini 3 Pro now scores 93%. This is superhuman: PhD experts answer 65% correctly, non-experts 34% *despite* web access.

But AIs are not omniscient. Humanity’s Last Exam (Phan et al., 2025) is the most difficult knowledge benchmark. Example questions from their website:

Consistent with other benchmarks, AI has moved from <5% to ~40% correct in one year. By end of 2026, this benchmark will likely be saturated.

AI Progress is Accelerating

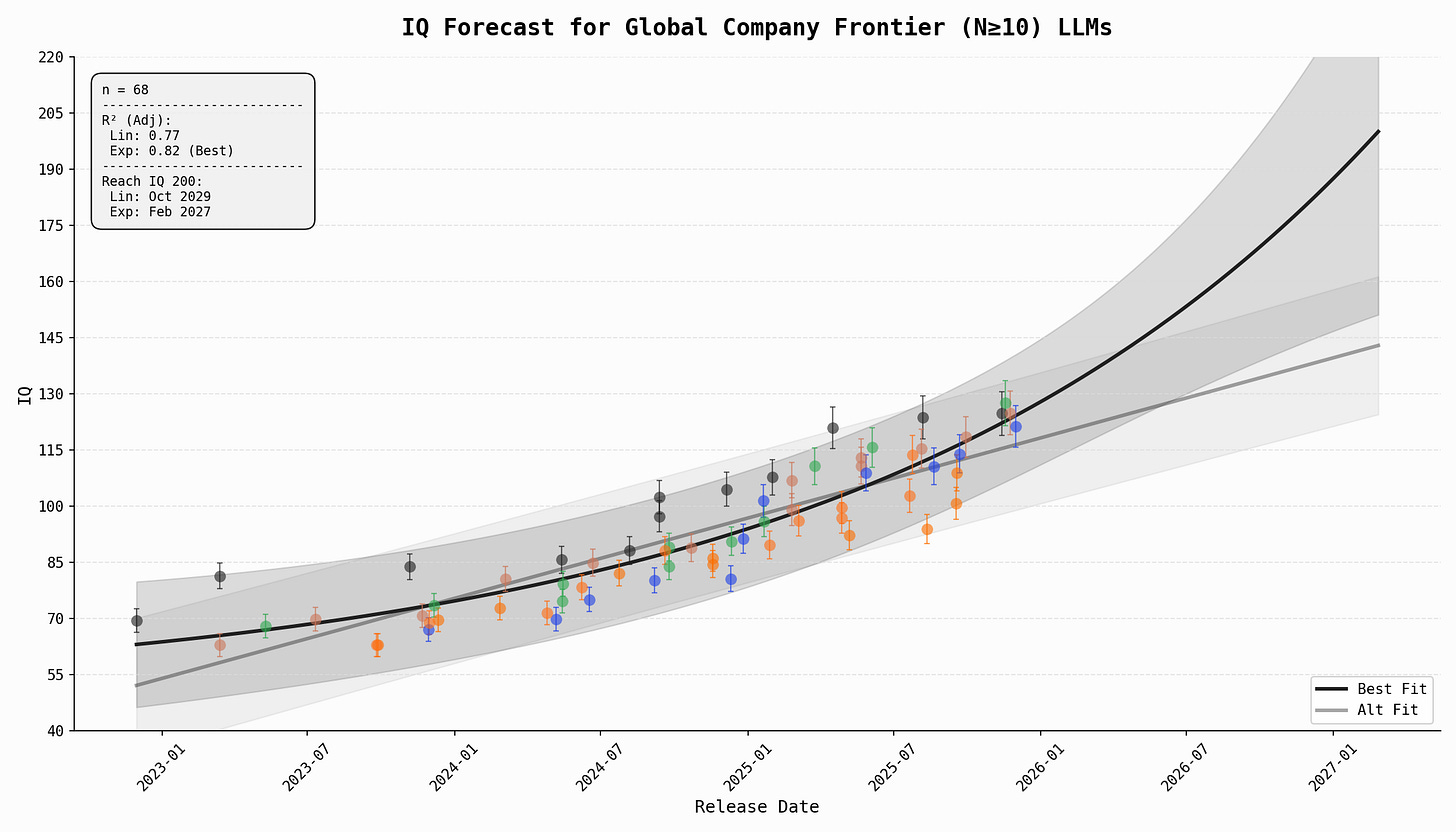

The rate of frontier AI progress has nearly doubled.

This was first noticed in METR’s time horizons, where progress has accelerated since early 2024.

This is likely real. Epoch AI reports the same pattern in ECI, their aggregate capability index.

Extrapolating METR forward: if the 80% success time horizon is ~30 minutes now, by early 2027 it will be 3 hours, by 2028 18.5 hours.

A work day is 8 hours; 18.5 hours is nearly half a week. By 2028, given ARC-AGI trajectories, AI’s problem solving will likely exceed above-average humans, and it will be an oracle of expert knowledge. By 2029, given agent-friendly environments with MCPs (tools to give itself context and interact with computers in text-based formats where it flourishes), it could automate most white collar work.

Top-20 global forecaster Peter Wildeford lays out similar estimates, mirroring these calculations. Projections vary despite trend consistency; AI Futures models AI milestones under dozens of parameters, estimating AI will complete 1 work year at 80% reliability by 2030.

The acceleration is unlikely to be due to AIs assisting researchers at coding experiments. Experiments are bottlenecked by throughput (compute) and quality (research taste). Labs are bottlenecked by compute (almost all goes to R&D). Since frontier lab researchers are likely 130-145 IQ, AI must supersede them in capability, and if continual learning is not solved, must also trump cumulative human-learnt intuition on AI research.

Cause of the Acceleration: Emergent Intelligence from Reinforcement Learning

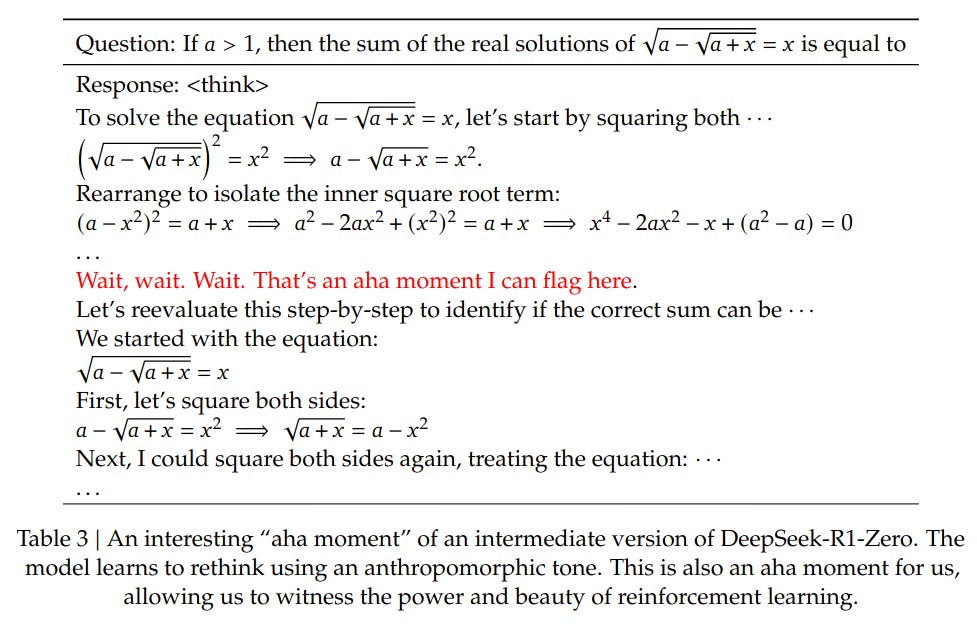

So why has progress accelerated? The answer is that there’s been a fundamental shift in how AIs are trained, from simply predicting the next word, to reinforcement learning, leading to emergent thinking.

To explain; in reinforcement learning, an agent (in the case of LLMs, an AI) tries actions in an environment like playing a game or solving a problem. The agent’s action is then associated with a reward or penalty based on the outcome; this might be losing a game (penalty) or correctly solving a problem (reward). Then, using mathematics4 the agent’s parameters are calibrated towards the configuration that resulted in the desired outcome. No labelled data is required for this, only self-play.

Reinforcement learning algorithms have previously produced superhuman performance. In 2016, DeepMind’s AlphaGo (Silver et al., 2016) defeated the world champion at Go, a game with more possible board positions than atoms in the universe. In 2022, Meta’s Cicero (FAIR et al., 2022) achieved human-level play in Diplomacy, a game requiring negotiation, deception, and long-term planning. These systems learned through self-play: millions of games against themselves, reinforcing patterns that led to victory, weakening patterns that led to defeat.

AIs are now trained in reinforcement learning environments, rather than just predicting the next word. Next word prediction produced sophisticated autocomplete; reinforcement learning produces reasoning.

Reinforcement learning caused this. Frontier models now train on verifiable tasks: for example, mathematics problems and coding exercises, where correctness can be verified with certainty. For math, the model’s answer is string-matched against ground truth. For code, output is executed against test cases in a sandbox. The model attempts problems, receives binary feedback (correct or incorrect), and adjusts its weights accordingly. This is Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR).

The optimizer of choice is Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO), proposed by DeepSeek in DeepSeekMath (Shao et al., 2024). For each problem, the model generates many candidate answers. Answers scoring above the group average are reinforced; those below are penalized. The group itself provides the baseline for comparison, eliminating the need for a separate critic model. This approach has become standard; as of late 2025, open-weight frontier models have not significantly deviated from RLVR and GRPO.

The result was phenomenal.

A new property emerged with no change in architecture: reasoning. Models, for the first time, on their own, without prompting, began to reason before answering questions. Nobody programmed this. This result was first published by DeepSeek R1-Zero (DeepSeek-AI et al., 2025), which termed it the “aha moment”.

Trained with pure reinforcement learning and no supervised examples, LLMs spontaneously started generating reasoning traces before answering. After this discovery, AIs began to be explicitly trained to encourage this behavior.

It’s worth reminding the reader how these models, and neural networks (the building blocks of LLMs), work.

These models generate text autoregressively: each word produced becomes context for the next. When the model writes a reasoning step, it attends to that step and builds on it. This is not recursion or a special architecture. It is roughly the same transformer used since the pre-reasoning era, trained differently.

Couple this with what we know about neural networks. Neural nets can approximate any function given enough parameters.5 Given that LLMs are now explicitly trained and validated on outcomes requiring intelligence, this heralds a paradigm shift. It is now reasonable to assert we are creating models with general intelligence.

The timeline of accelerating AI capabilities aligns with this development; OpenAI announced o1 (the first reasoning model) in September 2024; DeepSeek released R1 in January 2025. The acceleration in capabilities coincides roughly with the frontier labs implementing this technique at scale.

AI Progress Inevitability, Bubbles and Bottlenecks

Scaling Laws and Bottlenecks

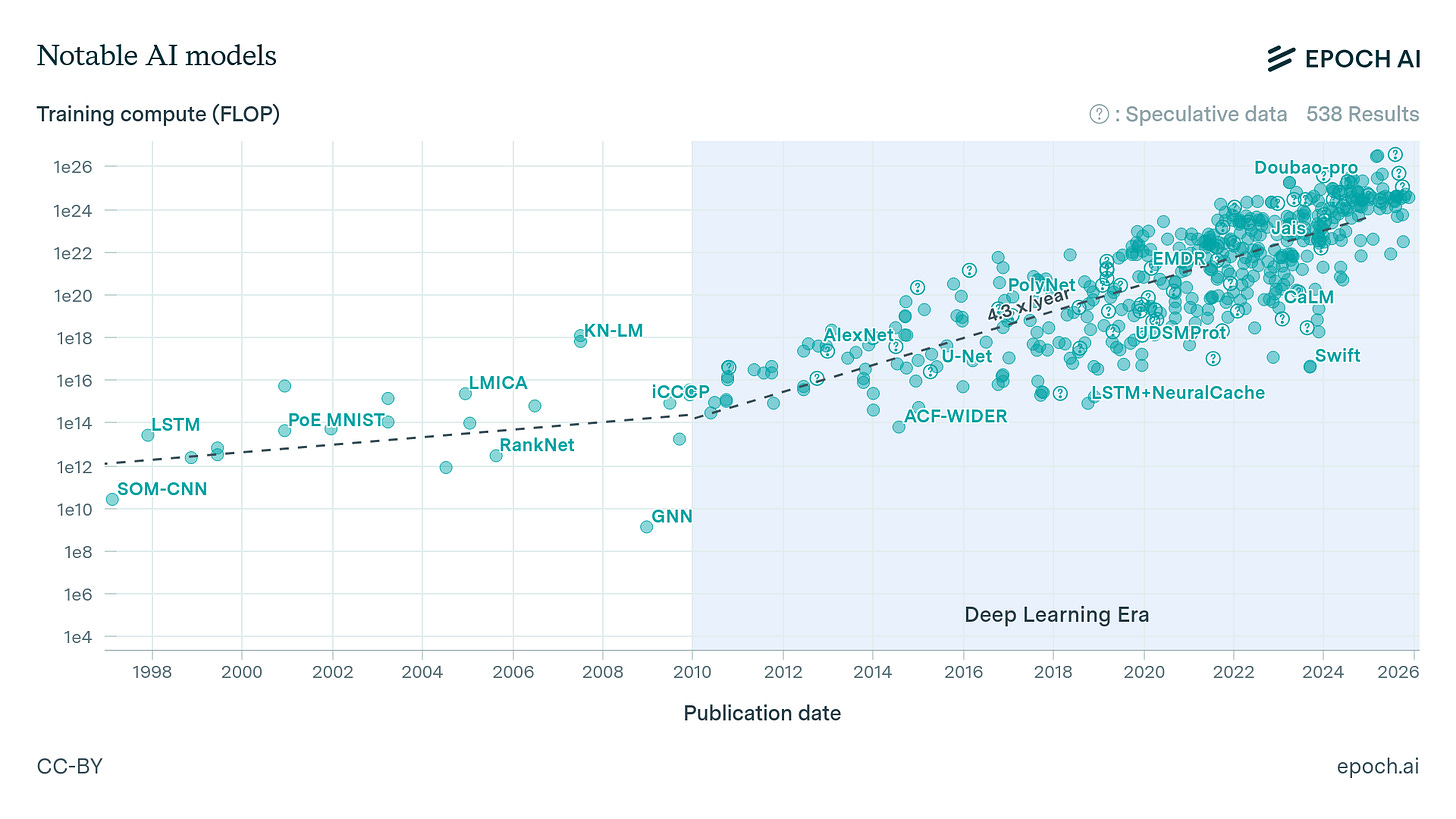

Training AIs has exponentially diminishing returns. For a given architecture, exponentially more compute is required to make the same gains. These are scaling laws, and they are universal. Even my Pedo AI saw diminishing returns in accuracy as it was fed more compute. This makes each generation of AI models exponentially more expensive to train.

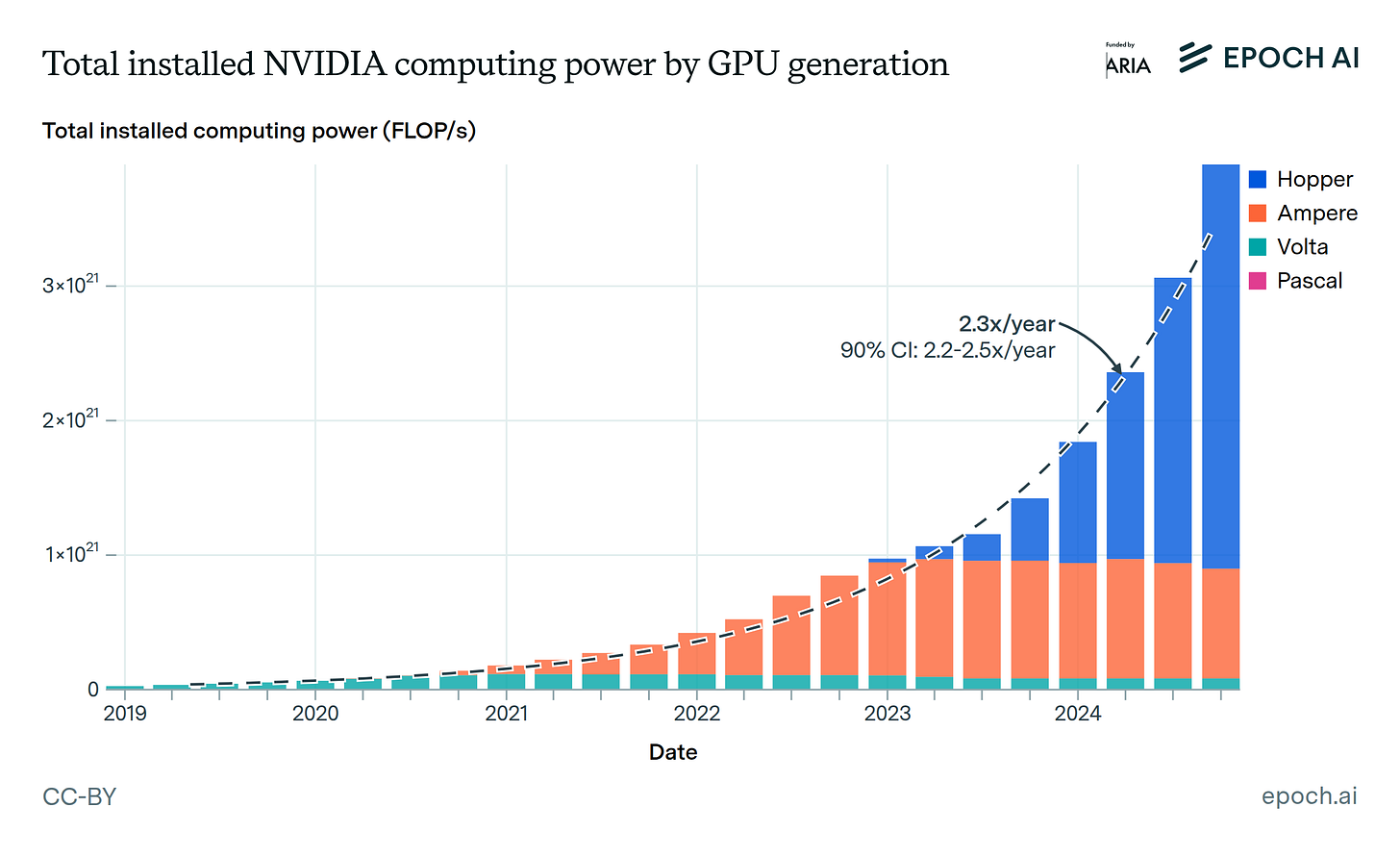

To accommodate this, training compute is increasing at 4.3x per year and installed capacity at 2.3x per year. However, there is valid speculation that capacity buildout will reach limits. Since compute growth has been a main driver of AI progress, slowing buildout would slow capability gains.

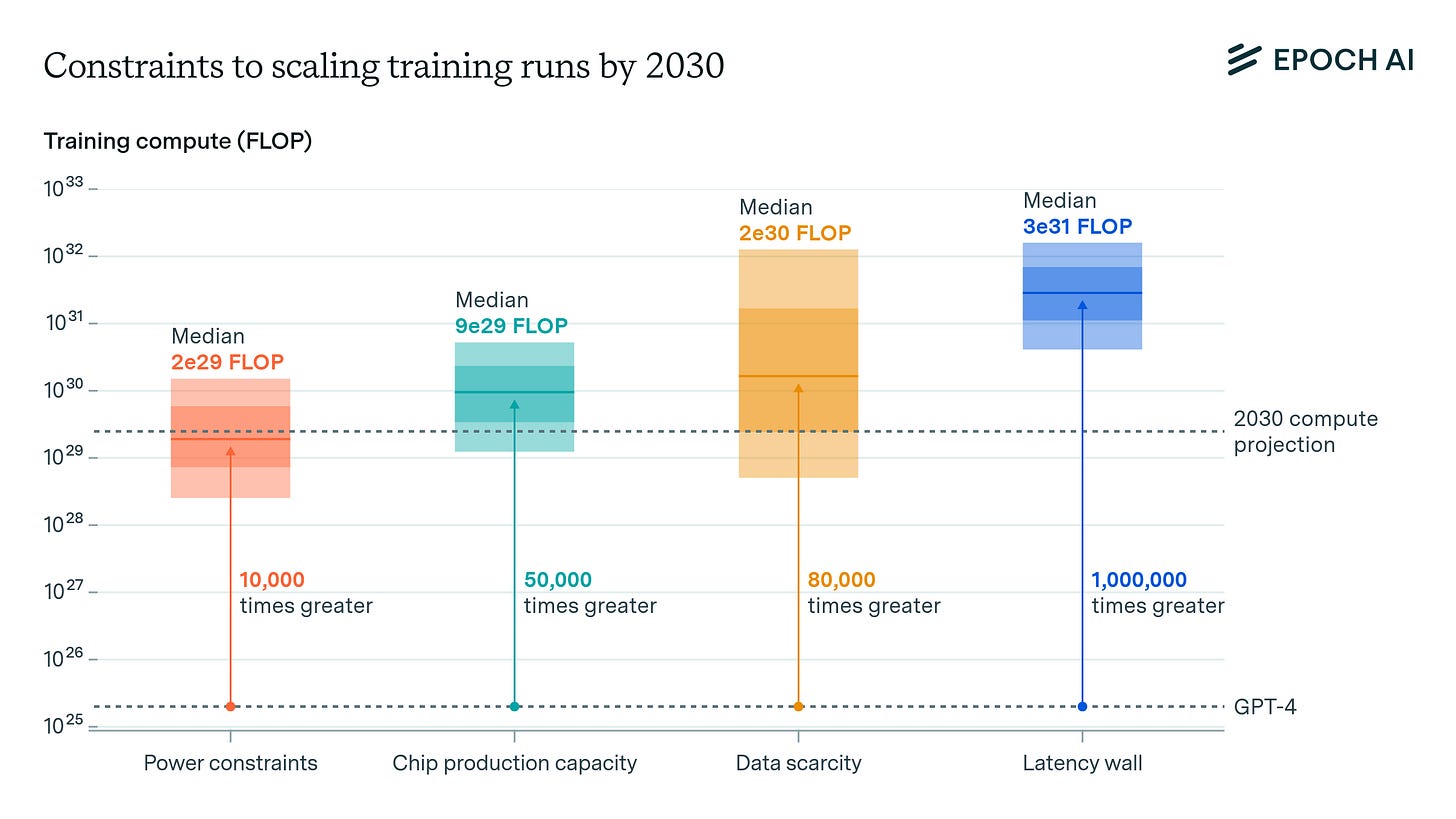

GPUs are power hungry. By the 2030s, AI demand for electricity will exceed the US power grid. Epoch provides estimates for other hard limitations, such as chip production capacity. Note that data scarcity is likely not an issue: since AIs are now trained through reinforcement learning, they self-generate data. The fear that AI would run out of text to predict no longer applies.

These are not hard barriers to AI progress for the next decade:

US energy stagnation is partially due to lacking demand. There hasn’t been economic ROI for developed countries to vastly expand their grids.

Should the US fail, China’s electrical grid is double that of the US, and their models are only ~8 months behind the frontier.

The cost of renewables and other energy sources is decreasing exponentially, making this bottleneck easier to solve.

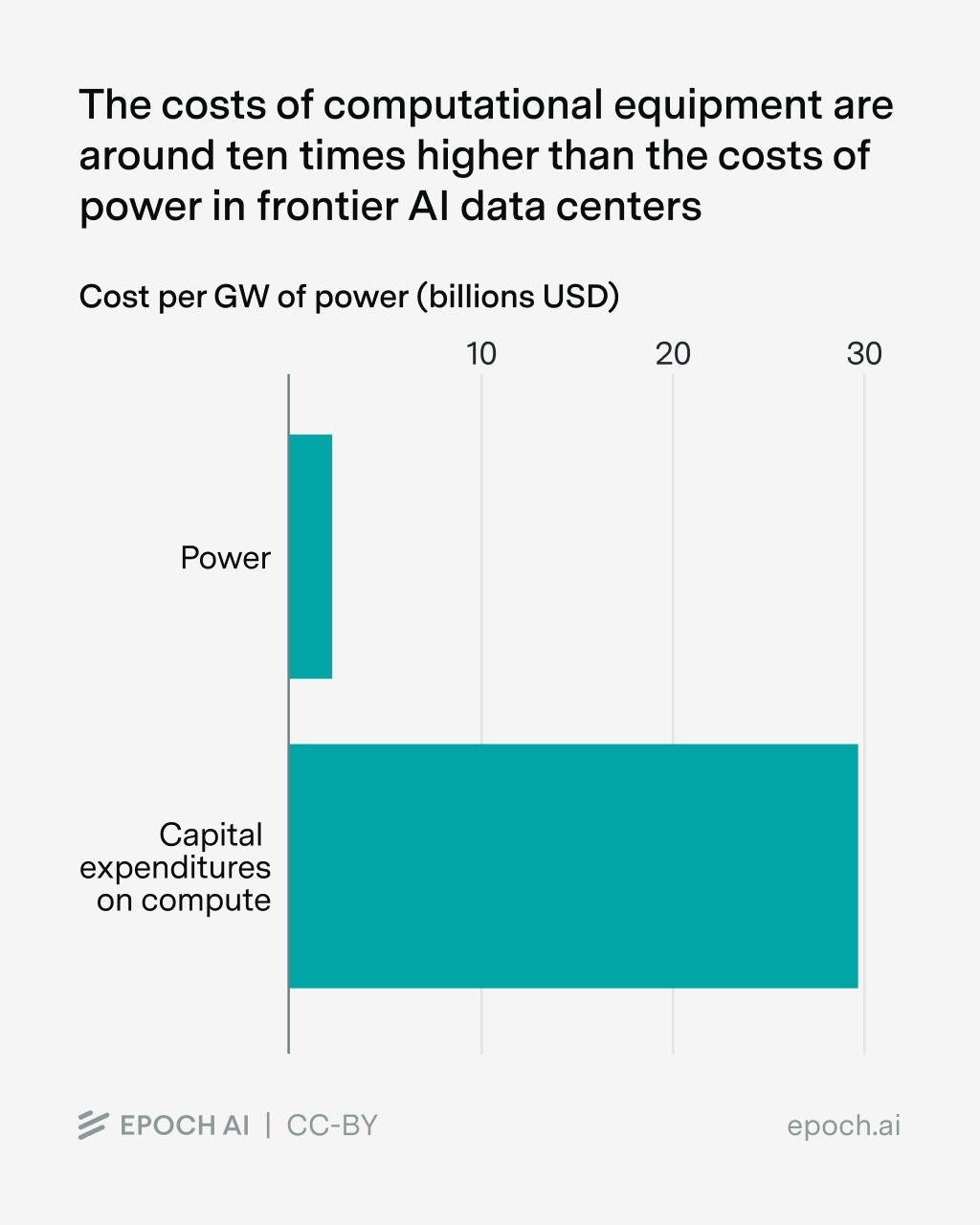

Power is a small expenditure relative to compute. AI companies could pay a premium for electricity, building their own power infrastructure.

Overall, this won’t be a massive bottleneck for the next decade, in agreement with Epoch.

However, if progress is 2-3x slower than forecasted despite capacity buildout, world-altering AI could take decades or require another architectural breakthrough. Given that progress has accelerated and how close we are to transformative AGI, this is possible but unlikely.

Bubble Woes

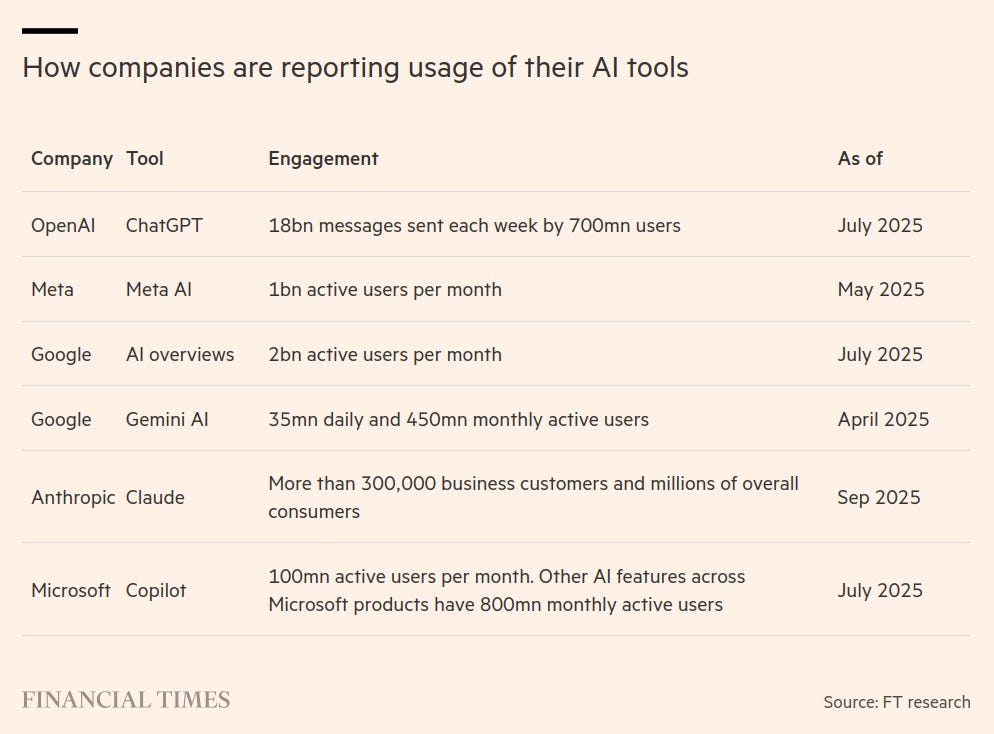

Compared to the Dot Com Bubble and Japanese Bubble, price-to-earnings ratios for AI companies are nearly half. From this FT article:

Revenue and valuation for AI companies are growing exponentially. For OpenAI, valuation is increasing at 3.0x per year, with revenue growing faster at 4.1x per year.

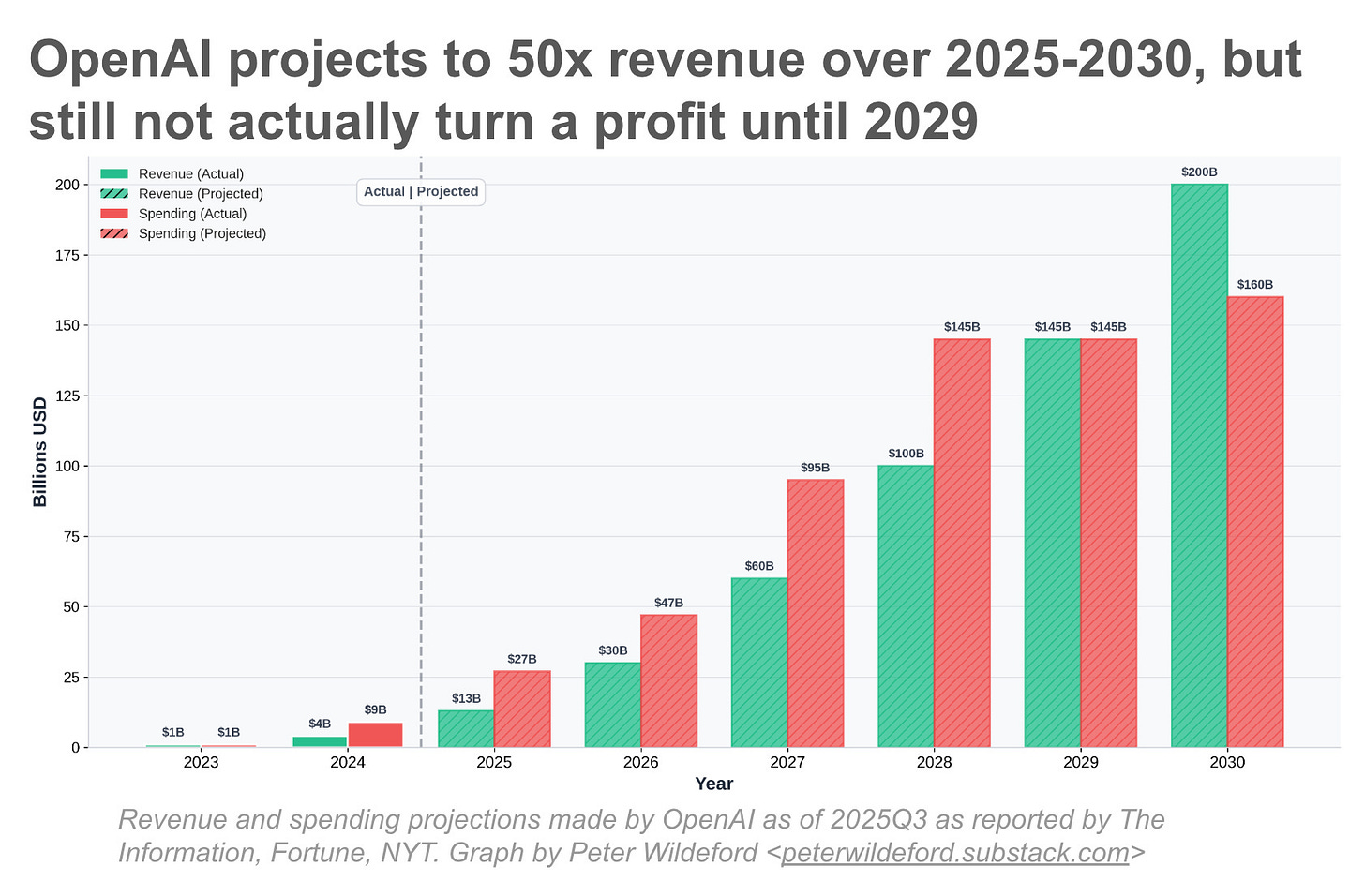

Despite this growth, parallels to previous bubbles exist. Telecommunications and railway companies were initially profitable with rapidly growing revenues. But they overinvested, supply outpaced demand, and the bubble popped. From Peter Wildeford’s substack:

Consider Britain’s Railway Mania of the 1840s. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, generated 10%+ annual returns and demonstrated railways could dramatically reduce transportation costs. This success triggered an explosive investment. Between 1844 and 1847, Parliament authorized over 8,000 miles of new rail construction.

Multiple companies laid parallel routes, each assuming they would capture market share. But a lot of the new routes were not profitable. When the crash came in 1847, thousands of investors lost fortunes. Yet the infrastructure remained valuable, powering Britain’s industrialization through the late 19th century. The technology thesis proved correct; the financial structure was catastrophic.

The telecommunications crash of 1997-2002 followed a similar pattern. The thesis was sound — explosive internet growth would require massive bandwidth capacity. Companies laid millions of miles of fiber optic cable, with industry capital expenditures reaching $600B from 1997 to 2001. But the simultaneous construction by competitors created catastrophic oversupply and a significant portion of the fiber was installed but unused. Though the fiber ultimately did end up seeing use over the next two decades, this was far too late for original investors.

Wildeford pushes back:

... unlike railway track sitting idle for years, AI data centers are being utilized immediately upon completion. OpenAI’s Abilene facility began running workloads as soon as capacity came online... The constraint is currently supply, not demand — which is why companies are aiming to build as much as possible.

AI infrastructure shows more flexibility than fiber optic cable. GPUs can run various workloads, data centers can host different services, and cloud capacity potentially retains value even if AI-specific demand disappoints.

Another bubble argument: AI expenses outweigh revenue. OpenAI won’t be profitable until 2029.

This is superficially relevant. Most spending is on infrastructure for compute, and the majority of OpenAI’s compute spending is R&D, not running models. If progress slowed, they could reduce buildout and switch to providing services. Even in a worst case, revenue streams are not threatened. This reinforces investor confidence.

Demand for the AI Economy

One might argue real AI use isn’t increasing, that it’s all hype. The opposite is true: AI demand is exploding across all sectors.

AI adoption has outpaced the internet, with billions of active users. Between 2024 and 2025, worker AI usage doubled.

Adoption extends beyond casual users to enterprise. The proportion of US businesses with paid AI subscriptions is consistently increasing: from ~26% to ~45% since the start of 2025.

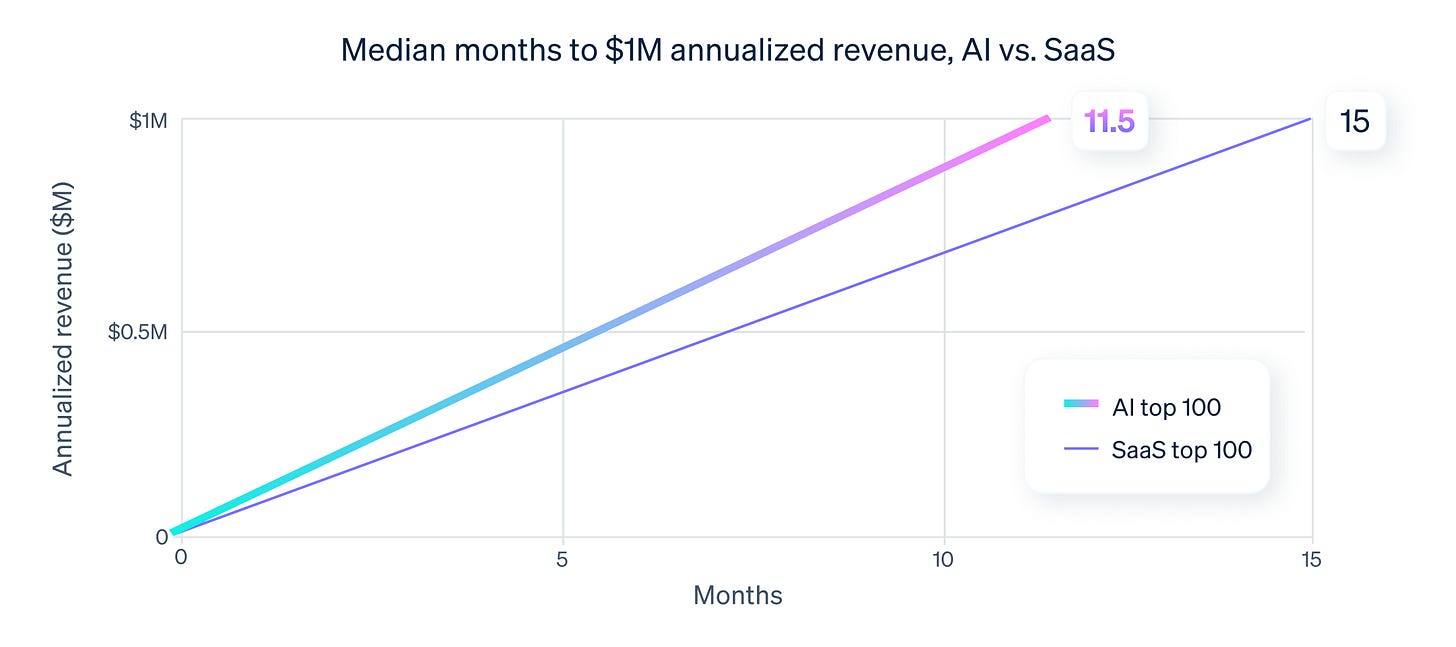

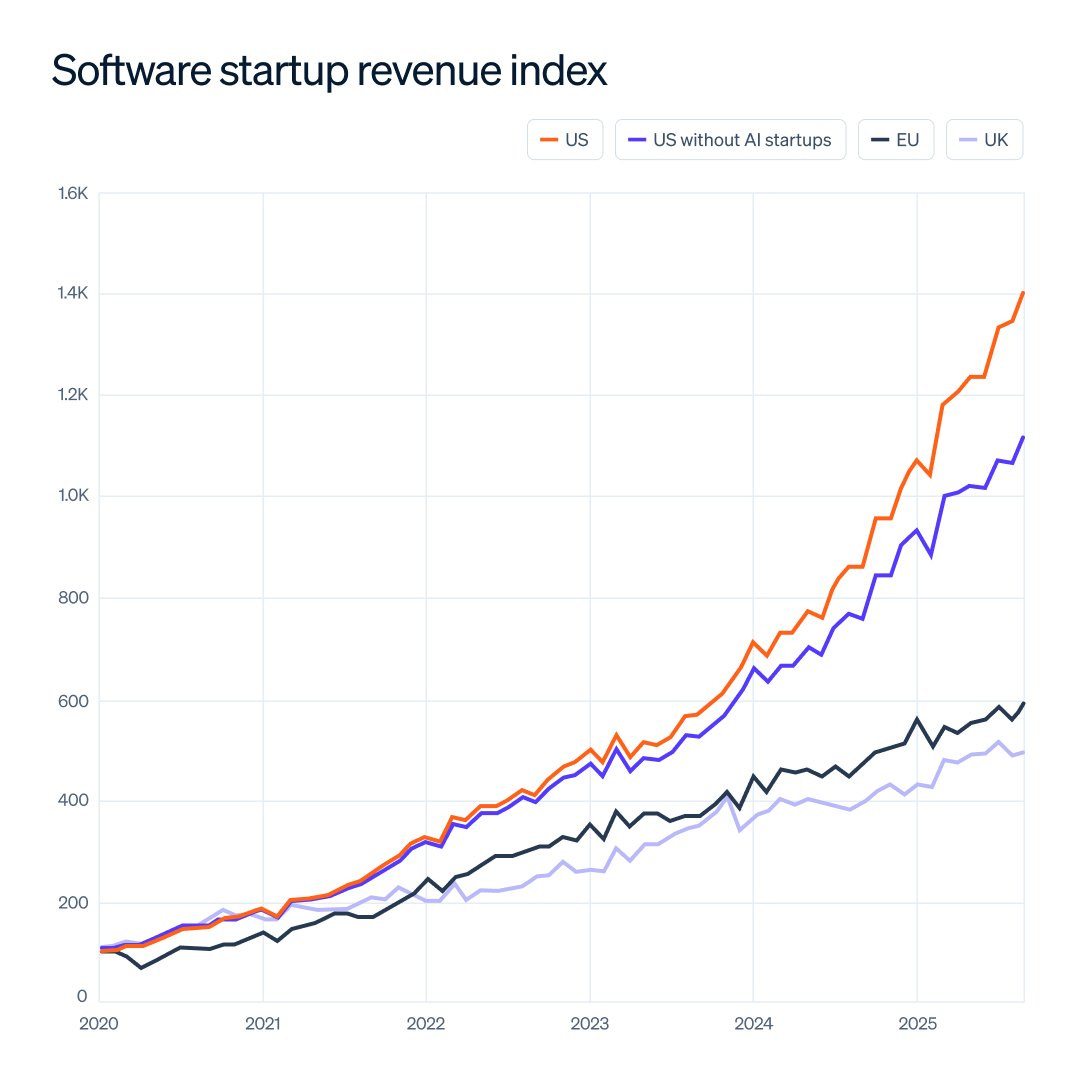

Businesses are profiting. According to Stripe, AI startups generate revenue sooner post-launch than traditional software startups.

This is confirmed by the decoupling in total startup revenue between AI and non-AI startups.

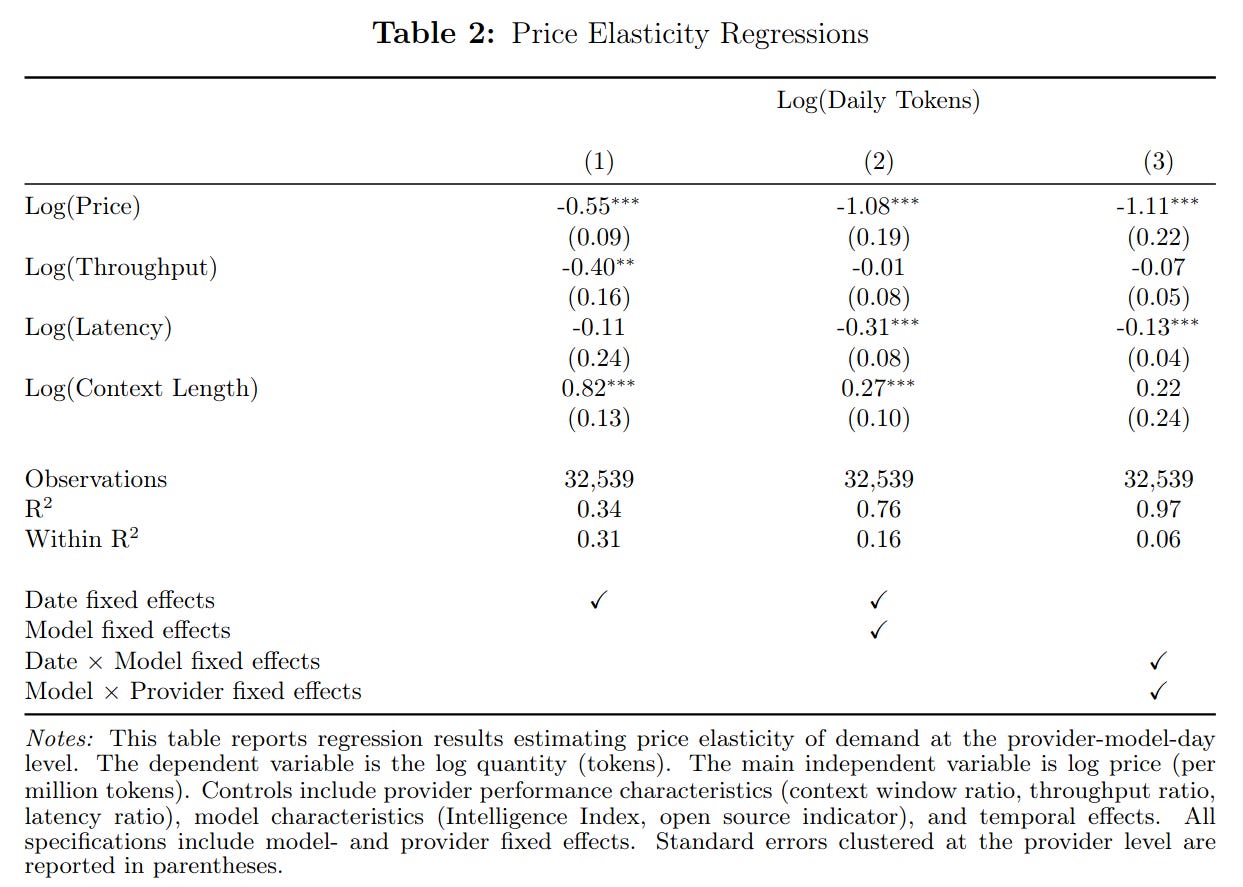

Price predicts demand between models. GPT-4 level models have declined in price by 1,000x in 3 years, with similar deflationary trends at other intelligence levels. We would expect demand to increase accordingly (Demirer et al., 2025).

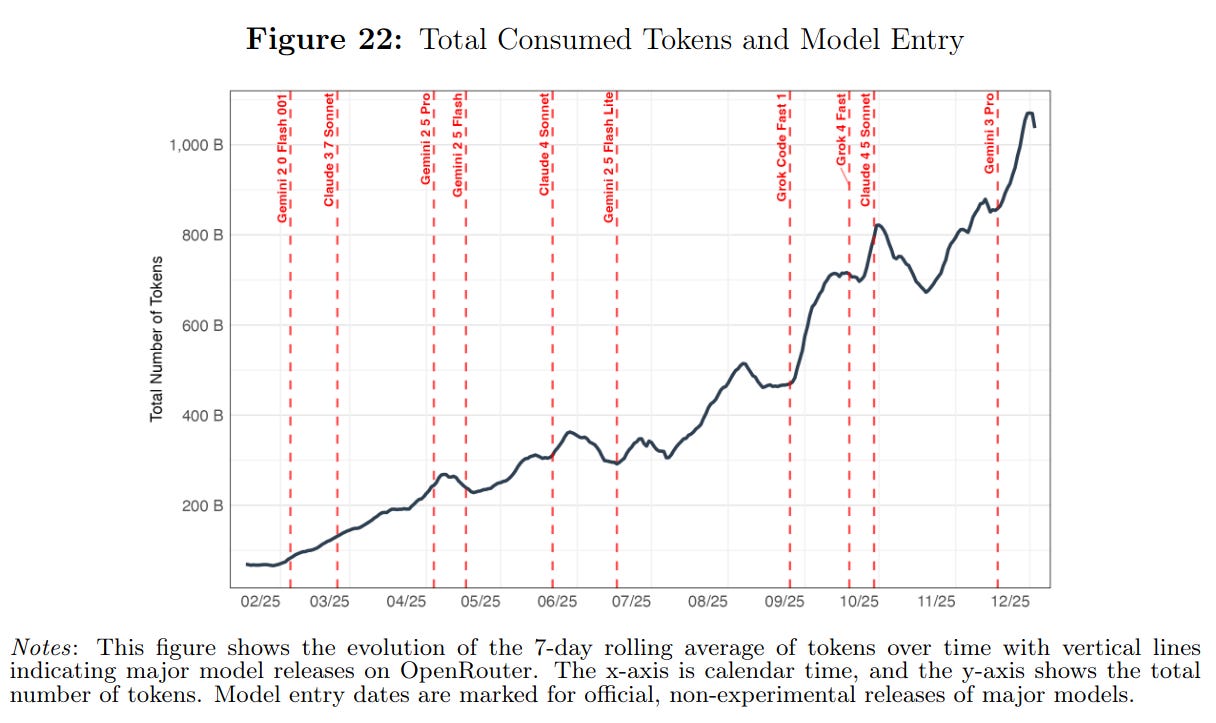

This is what we see. Menlo Ventures estimates enterprise API spending on generative AI increased from $3.5 billion to $8.4 billion in six months. OpenRouter reports token output increased 9x in 8 months, now at 1 trillion tokens per week (roughly 750 billion words).

This demand is driven by genuine productivity, not hype. From 100,000 conversations with Claude, Anthropic estimates timesavings of up to 80% on many tasks. This corroborates our earlier article showing AI improves job performance even with weaker models.

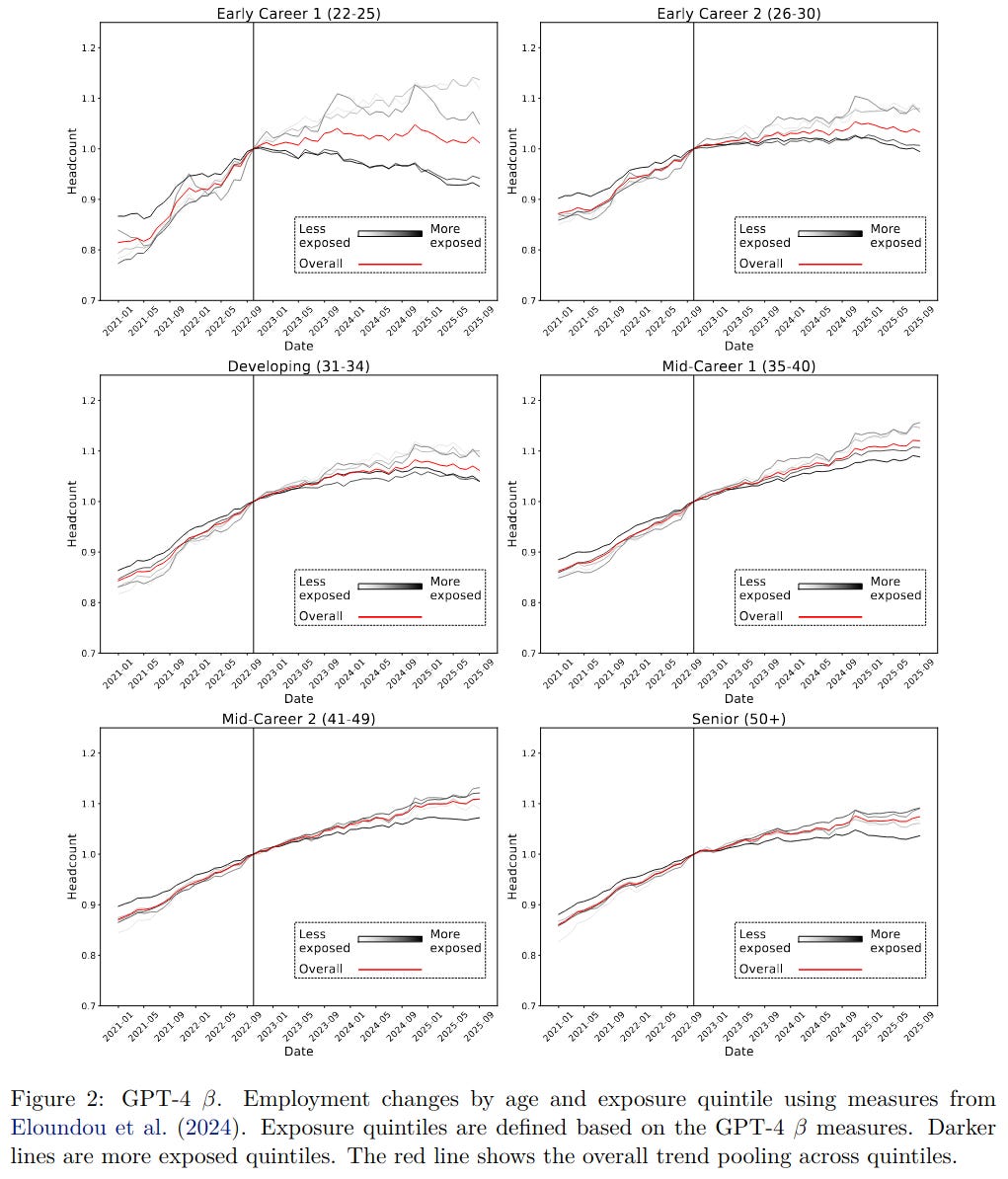

This has quantifiable effects on hiring. Companies are starting to prefer AI over graduates. Occupations more exposed to AI show larger headcount declines for those starting their careers (Brynjolfsson et al., 2025).

So overall, the AI economy is here, arriving faster than most impactful technologies in history. Adoption is real, productivity gains are measurable, and demand is outpacing supply.

Conclusion

AI possesses general intelligence. Using the same statistics behind IQ tests, we showed AI’s capability structure parallels human g: the first principal component explains similar variance (44% for humans, 40-50% for AI), and performance correlates across benchmarks just as it does across human cognitive tests.

On key benchmarks, progress has been dramatic. ARC-AGI went from 18% to 86% in one year, now matching average human performance at a fraction of the cost. METR’s time horizons are doubling every 4 months. Humanity’s Last Exam improved from <5% to 40%.

This acceleration stems from a paradigm shift: reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards, which produced emergent reasoning without anyone programming it. The architecture hasn’t changed since GPT-2. What changed is training AI directly on problem-solving rather than next-word prediction.

Scaling bottlenecks exist but are surmountable. The bubble arguments fail: P/E ratios are half those of dot-com, revenue is growing faster than valuation, enterprise spending is doubling every six months, and worker adoption doubled year-over-year.

My Personal Closing Thoughts

I tried avoiding making forecasts and year-by-year predictions of the future, because I want you, the reader, to make your own inferences.

However, I am of the opinion that, given the evidence, better than human-level AI across >95% of domains will arrive within 5-10 years.

Thus, in the past few short years, my expectations for the future have been completely overhauled, updating to this reality. Although AI alignment was not covered in this article, there is also concerning evidence that a world in which these capable systems work against humanity is possible. Some consider human extinction likely or even certain.

As a user since GPT-4 and an early adopter of agentic interfaces like Cursor and Claude Code, I’ve seen the time horizons expand firsthand. It could barely write a single function a few years ago, and it would be very slow at doing so. Then it could write sections of scripts and some middling logic. Then the entire script, and quickly too. Now it can interact with entire codebases, writing and executing scripts on my machine directly rather than through a browser.

This all happened in about two years.

For me, this is as real as it gets.

When I used to ponder issues humanity may face (e.g. dysgenics, population decline, etc), I could have a large degree of detachment. After all, the problems were theoretical, numbers on academic papers. Nothing I could see with my own eyes as I have done and continue to see with AI.

Furthermore, even if I could experience these other issues, its possible culmination into a civilizational collapse was lifetimes away, or just uncertain given the timescales. A lot can happen in a few decades. Humanity’s ability to innovate captures that uncertainty, as I have written about.

When speaking to normies (when appropriate) about these future issues, the response is always a variant of “that’s cool bro, so anyway”, and admittedly, that’s the correct response to large and possibly dubious claims. For me, they are also somewhat of a novelty; my telling them was driven by interest and a genuine curiosity to hear their opinion (if they were likely to have one), rather than any civic duty to “spread the word”.

But with AI, that same response hits different. I can’t help but think there’s a disconnect between what I really believe to be important and what others know.

For example, two large polls show Americans rank AI as the lowest threat and voting priority. Another survey shows only 28% even know what AI is, most think it’s a tool looking up answers in a database.

Unfortunately for the unaware, reality can only be ignored for so long, regardless of what the general population may think or feel about AI. A new age is dawning.

”Just because you do not take an interest in politics doesn’t mean politics won’t take an interest in you.”

— Pericles

References

Brynjolfsson, E., Chandar, B., & Chen, R. (2025). Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved January 2, 2026, from https://digitaleconomy.stanford.edu/publications/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/

DeepSeek-AI, Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q., Ma, S., Wang, P., Bi, X., Zhang, X., Yu, X., Wu, Y., Wu, Z. F., Gou, Z., Shao, Z., Li, Z., Gao, Z., … Zhang, Z. (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning (No. arXiv:2501.12948). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12948

Demirer, M., Fradkin, A., Tadelis, N., & Peng, S. (2025). The Emerging Market for Intelligence: Pricing, Supply, and Demand for LLMs (No. w34608; p. w34608). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w34608

Ho, A., Denain, J.-S., Atanasov, D., Albanie, S., & Shah, R. (2025). A Rosetta Stone for AI Benchmarks (No. arXiv:2512.00193). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2512.00193

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2017). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R (Corrected at 8th printing 2017). Springer.

Krautter, K., Lehmann, J., Kleinort, E., Koch, M., Spinath, F. M., & Becker, N. (2021). Test Preparation in Figural Matrices Tests: Focus on the Difficult Rules. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 619440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.619440

Kwa, T., West, B., Becker, J., Deng, A., Garcia, K., Hasin, M., Jawhar, S., Kinniment, M., Rush, N., Arx, S. V., Bloom, R., Broadley, T., Du, H., Goodrich, B., Jurkovic, N., Miles, L. H., Nix, S., Lin, T., Parikh, N., … Chan, L. (2025). Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks (No. arXiv:2503.14499). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.14499

Meta Fundamental AI Research Diplomacy Team (FAIR)†, Bakhtin, A., Brown, N., Dinan, E., Farina, G., Flaherty, C., Fried, D., Goff, A., Gray, J., Hu, H., Jacob, A. P., Komeili, M., Konath, K., Kwon, M., Lerer, A., Lewis, M., Miller, A. H., Mitts, S., Renduchintala, A., … Zijlstra, M. (2022). Human-level play in the game of Diplomacy by combining language models with strategic reasoning. Science, 378(6624), 1067–1074. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ade9097

Phan, L., Gatti, A., Han, Z., Li, N., Hu, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, C. B. C., Shaaban, M., Ling, J., Shi, S., Choi, M., Agrawal, A., Chopra, A., Khoja, A., Kim, R., Ren, R., Hausenloy, J., Zhang, O., Mazeika, M., … Hendrycks, D. (2025). Humanity’s Last Exam (No. arXiv:2501.14249). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.14249

Shao, Z., Wang, P., Zhu, Q., Xu, R., Song, J., Bi, X., Zhang, H., Zhang, M., Li, Y. K., Wu, Y., & Guo, D. (2024). DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models (No. arXiv:2402.03300). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.03300

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., Van Den Driessche, G., Schrittwieser, J., Antonoglou, I., Panneershelvam, V., Lanctot, M., Dieleman, S., Grewe, D., Nham, J., Kalchbrenner, N., Sutskever, I., Lillicrap, T., Leach, M., Kavukcuoglu, K., Graepel, T., & Hassabis, D. (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529(7587), 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

Xie, T., Zhang, D., Chen, J., Li, X., Zhao, S., Cao, R., Hua, T. J., Cheng, Z., Shin, D., Lei, F., Liu, Y., Xu, Y., Zhou, S., Savarese, S., Xiong, C., Zhong, V., & Yu, T. (2024). OSWorld: Benchmarking Multimodal Agents for Open-Ended Tasks in Real Computer Environments (No. arXiv:2404.07972). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.07972

ECI uses a sigmoidal IRT model; g is typically extracted via factor analysis. The difference is minimal: both extract a single latent dimension, human scores cluster mid-range where the sigmoid approximates linearity, and the correlation between factor-analytic g and ECI approaches unity.

MTurkers are Amazon Mechanical Turk workers, typically paid below minimum wage. The average MTurker is from the developing world, roughly ~80 IQ.

The “human panel” comparison is misleading: a question is marked correct if at least one human solved it. The 100% threshold asks whether AI is smarter than all humans combined, which is clearly not true. For now.

Backpropagation and gradient descent.

A layman’s proof is here (James et al., 2017, pp. 404-406).

Will work on a response to this. My thesis is that, as demand for nerds decreases, humanity will be optimized for war fighting. Robots are energetically efficient, and the limitations on battery size and weight cannot be overcome by just building larger data centers.

Thank you for taking the time to cover this topic. It is always a joy to see political commentators of a certain leaning taking steps into AI discourse.

With that being said: likening RLVR to self-play is simply wrong. RLVR is infinite rollout data, not infinite evaluators. There is no meaningful (public) scheme for pure self-play bootstrapping of text intelligence ala alphazero.

Like alphago, modern LLMs need pretraining (human text supervision) and handmade environments (human labor *per-task-type*). There is no working notion of an "environment for everything" that permits unbounded ECI growth; the potential for AI capabilities growth in 2025 is bounded by the definitions of its evals (which, admittedly, is still a very wide bound, but not one that fully circumscribes human capabilities); evals which are still primarily developed by human labor. You can't LLM-as-a-judge your way to corporate secrets or visuomotor policies.

Of course, I fully expect the aforementioned bottleneck to be solved soon. But this is the most important miss of the article, and I hope as many readers note it as possible.

Other notes below.

---

ECI and other "AI IQ" indices are also naturally tainted by the same issue of [what's measured] -> [what's evaluable] -> [what's RLVR'd]. They don't give the same assurance of generalizability that human IQ does -- you *can* actually train on every exam for an AI, and there is no meaningful bottleneck for how much compute a single model can throw at a problem.

That doesn't mean ECI or other benchmarks aren't meaningful, of course. A lot is getting automated.

The issue with AI corporate financials isn't the rate of rev vs cap growth, its the base ratio. OpenAI's P/E ratio is absurd matter how you measure it; the "bubble" is its current multiple rather than the rate of change.

Importantly, *if the current trendlines continued for 3 years*, OpenAI would have a P/S of ~25 @ 22.5T (and a still negative P/E by their own projections!). A downturn in investor sentiment in the AI sector in 2028 would necessarily lead to a massive market cap contraction. Even with amazing technology, OpenAI needs a far larger rev multiplier to justify its position.

The comparisons of chatgpt growth to other historical technologies are always absurd. Especially in the case of the internet -- the internet is ChatGPT's distributor; it's hardly a surprise the former took far longer to bootstrap comms than the latter.

Comparing startup rev in isolation is nasty. No normalization between investment and rev differences, when VCs naturally pump AI startups with far more resources in the current context. Although I still support Collison's interpretation, it's in poor taste to use it as evidence-of rather than to-be-explained.

Strongly agree that, despite everything I've mentioned above, AI policy is the most important&impactful political issue of our era.